AS the lone figure methodically ascends the towering tree, each step seems to defy gravity, ropes gently guiding his ascent. My heart clenches in my chest as I watch, a silent prayer on my lips, knowing all too well the risks involved. Every movement feels like a heartbeat; each tug on the rope a reminder of the precariousness of this endeavour.

Not too long ago, the air was shattered by the thunderous sound of a branch snapping, a deafening CRACK that echoed through the forest. It plummeted earthward with terrifying force, missing us by a hair's breadth. "Move away!" bellowed one of the climbers, urgency lacing his voice as he directed us to safety.

Yet here we are again, holding our breath, hoping against hope that this time everything will go smoothly. But amidst the tension, there's a quiet awe; a reverence for the bravery of those who dare to reach for the sky, even when the earth threatens to pull them down.

Eddie Ahmad finds himself teetering atop the tall Keruing Bukit he bravely ascended. Yet, amidst the precarious balancing act, his determination remains unwavering. His mission is clear: to create a haven for the hornbills whose survival hinges on the availability of suitable nesting sites.

With the scarcity of tall trees boasting natural hollows, the hornbills face an increasingly daunting challenge. It's in these critical moments that external support becomes imperative for their continued existence.

Enter the introduction of nest boxes, a human-engineered remedy crafted to counteract the loss of their native habitats due to deforestation and the felling of cavity-rich trees.

Eddie and his team from HUTAN/KOCP — a conservation non-governmental grassroot organisation based in Kinabatangan, Sabah — have ventured into Langkawi, Kedah. Among them are Mahatir Rataq, Selamat Suali and Ahmad Sapie Kapar, seasoned climbers with a shared commitment to wildlife preservation.

Their mission? To join forces with Gaia, a social enterprise dedicated to hornbill conservation, and install an artificial hornbill nest box in the heart of this coastal primary rainforest, a vital endeavour aligned with The Datai's Wildlife for the Future initiative.

This programme — an integral part of the luxury resort's ethos — is dedicated to safeguarding Langkawi's natural heritage and aims to establish a sustainable habitat, ensuring the continued presence of these captivating birds in their island home.

"Saya sudah biasa… (I'm used to it)," Eddie calmly replies when I inquire about his ability to stay composed while navigating the trees. Despite the challenges — from snapping branches to sudden gusts of wind, and even encounters with angry hornets while suspended from ropes — the wiry, diminutive man remains unfazed.

It's all in a day's work for the 47-year-old, who sits across me later with a slight smile on his weather-beaten face.

EARLY MEMORIES

"At first, I knew nothing about conservation, but I learnt on the job. I'm still learning," confesses Eddie, the Wildlife Survey and Protection Unit (WSP) manager at HUTAN.

His candour is refreshing. Grounded, pragmatic and true to his kampung roots, he's a typical salt-of-the-earth kind of guy, thriving on hands-on work — a trait shared by men hailing from rural communities.

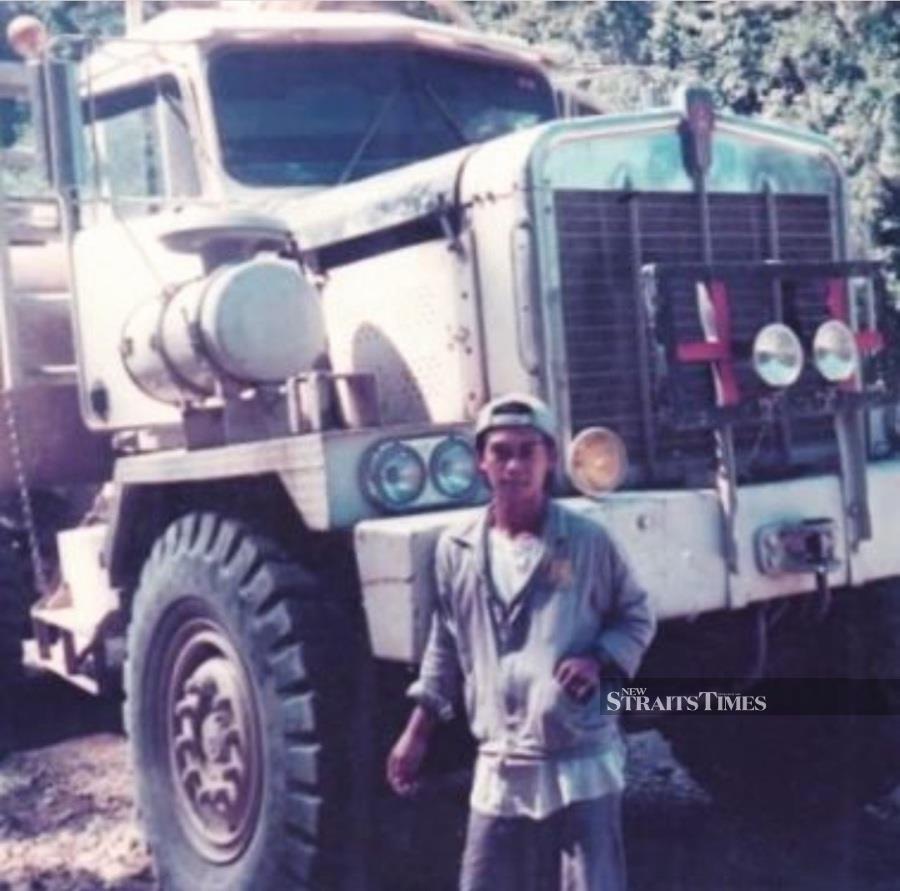

Of Sungai-Iban descent, Eddie was born in Sukau, Sabah, but spent most of his childhood at logging camps. Grinning wryly, he explains: "My father was a construction worker, who helped build access roads through the forest for logging machinery and trucks to go through."

Growing up in a logging camp in Keningau, Sabah, the young boy was surrounded by dense forests. "I knew nothing about wildlife then," he recalls ruefully, adding: "Ayah buat jalan (my father built roads). That's all I knew."

His memories are dominated by scenes of cleared forests, the cacophony of machinery and rows of timber on barren patches of land. Red dust, lumbering trucks and the feeling of walking through the camp with mud-caked shoes are etched into his mind.

The young boy later returned to his village to continue his secondary studies, progressing from Form 1 to Form 5. One of the most profound memories he shares with me is witnessing captive rhinoceroses being transported out of their shrinking forest which was being cleared.

Little did he know then, as he gazed upon those majestic creatures, that they were harbingers of an impending tragedy — the extinction of Sumatran rhinoceroses, lost forever to the wild. "I didn't understand the weight of that moment," he confesses quietly.

Upon completing Form 5, Eddie once again accompanied his father to another logging camp — this time, in Kapit, Sarawak. "It was different kind of forest," he shares. "More mountainous and higher in elevation. It was here that I landed my first job!"

The 19-year-old was eager to be a mechanic. "I wanted to find work at the camp!" he confides. The large trucks, lorries and heavy machinery looked imposing, but Eddie was undeterred.

"Lu kuat angkat taya lori ka? (Are you strong enough to lift the lorry tyre?)" the foreman asked him doubtfully, eyeing his diminutive size. "To be fair, the tyre was almost as tall as I was!" Eddie recounts, laughing. "Belum cuba, belum tahu! (If you don't try, you won't know!)" he told the foreman.

The plucky youth landed the job and spent five years working as a mechanic. "It was hard work," he says. "I can't recall much except for the spanner, those tyres and engine oil! That was my life then."

What happened after five years? I ask.

He sits back and sighs, his face clouded with sorrow.

In 1999, Eddie's father fell ill and was eventually diagnosed with liver cancer. He passed away the following year and was laid to rest in Kapit. His grieving son made the decision to return to Sukau soon after.

"Banyak kenangan di situ dengan ayah saya… (There were too many memories in Kapit with my father)," he explains, voice heavy with emotion. Clearing his throat and wiping his eyes, Eddie adds: "I was very close to my father. He was my best friend."

He exhales shakily and falls silent.

NEW BEGINNING

Returning to Kampung Sukau brought a sense of solace for Eddie and his mother, providing the comfort they needed to heal. With a pressing need for employment, Eddie began applying for jobs, casting a wide net and applying for any opportunity that crossed his path. His determination was unwavering; he was prepared to tackle any job, no matter how humble or challenging. "I was willing to do anything," he recalls.

His journey took an unexpected turn when he secured an interview with HUTAN, largely thanks to his cousin's connection with the NGO. "I knew nothing about the work. All I observed was the fact that the field officers would enter the forest in the morning and would only show their faces once it was dark. And the cycle would repeat every day," he describes, chuckling.

HUTAN's close ties with the local community around Kinabatangan meant that its conservation efforts were deeply rooted in grassroots involvement. This symbiotic relationship led to a significant number of villagers either working directly with the NGO or actively contributing their support to its various conservation programmes. "Many people in my kampung was working with HUTAN," says Eddie.

In March 2001, his journey with HUTAN began, marking the start of his immersion into the world of conservation. Despite his initial lack of knowledge, he was eager to absorb everything he could.

Turning down other tempting job offers — including a government position that would have required him to leave Sukau — Eddie remained steadfast in his commitment to HUTAN.

His decision was deeply rooted in his sense of duty towards his mother. As her only child, he felt a profound responsibility to stay by her side. "Saya perlu kekal di rumah, jaga ibu (I need to remain at home to take care of my mother)," he explains.

Among the earliest skills Eddie acquired at HUTAN was the use of Global Positioning System (GPS) technology and fieldwork techniques. Equipped with GPS devices, he ventured into the dense forests of Kinabatangan, learning to navigate and map out critical areas for conservation efforts. Fieldwork became second nature to him as he honed his abilities to observe, document and analyse the natural environment around him.

His interest and talent for studying maps not only facilitated his navigation through the intricate terrain of Kinabatangan, but also fuelled his curiosity about the broader landscape and its ecological intricacies.

A NATURE ADVOCATE

Eddie's introduction to the fascinating world of wildlife came through his involvement in the Kinabatangan Orangutan Conservation Programme (KOCP), established by HUTAN in collaboration with the Sabah Wildlife Department. With the full support of these organisations, the KOCP aimed to protect and conserve the critically endangered orangutan population in Kinabatangan.

"We'd enter the forest early morning to track these great apes and leave once they made their nest. Only then we'll return home," he recalls. Their daily routine involved carefully following the movements of these magnificent creatures, observing their behaviour and habitat preferences. With patience and perseverance, they would shadow the orangutans until they settled down to construct their nests for the night.

Orangutans, like all great apes, exhibit remarkable intelligence and adaptability. Each day, they meticulously fashion new nests from branches and foliage, a behaviour that reflects their nomadic lifestyle and their need for secure resting places. Rarely returning to their old nests, orangutans move through the forest canopy, constantly seeking out fresh locations to spend the night.

Eddie then hilariously mimics the orangutan calls and tells me, amidst bouts of laughter, how the agitated animals would fling branches at the observers. But eventually, they got used to their human companions.

"We soon learnt to differentiate between them, and we named them. There was Jenny and the other one was Maria. It wasn't difficult. After all, humans and orangutans share approximately 97 per cent of their DNA!" he shares blithely.

In that forest, amidst the lush greenery and the playful antics of orangutans, Eddie found more than just a job — he found a passion.

Tone wry, Eddie reflects: "From logging camps to wildlife conservation… quite the turnaround, isn't it? It's like I've gone from being part of the problem, to becoming the solution."

A pause, and he continues: "Saya rasa bersalah dan saya harus ambil tanggungjawab. (I feel guilty and I have to take responsibility). I have to tell people that what I did in the past (working in logging camps) was wrong and shouldn't be emulated."

Now, as a wildlife protector, Eddie dedicates his time to safeguarding wildlife and addressing the challenges of human-wildlife conflict, a consequence of increasing forest fragmentation. Armed with a hailer, clapping hands loudly and yelling, or even using a modified "cannon", he and his team guide rogue elephants back into the safety of the forest.

They've also constructed animal crossings over rivers and estuaries, ensuring safe passage for wildlife. Additionally, scaling tall trees to install artificial nest boxes is just one of the many tasks Eddie undertakes.

In his role as a wildlife warden, he ventures into the forests to enforce wildlife laws, ensuring that regulations are upheld and wildlife habitats remain protected.

"These days, we're determined to preserve whatever forest remains," he asserts, emphasising the urgent need for action.

Despite the risks inherent in his work, the resilient man doesn't dwell on the potential costs. Instead, he poses a poignant question: "If we don't do this, who will?"

Tone sombre, Eddie reflects on the changes he's witnessed in the landscape due to forest degradation. He remembers a time when Sungai Kinabatangan flowed clear and pristine, a haven for wildlife and locals alike. But now, the once-clear waters are tainted by pollution, a stark reminder of the environmental challenges facing the region.

In a heartfelt moment, the father-of-three shares a personal anecdote that underscores the impact of this pollution on his family. He recalls the necessity of buying mineral water to make milk for his newborn baby, highlighting the harsh reality of living amidst environmental degradation.

"This is why I'm committed to what I do," Eddie concludes softly. "I'm not just passionate about my work, I'm doing it for my children as well. What kind of world will they inherit as they grow up? I have to ensure their future and that of the generations to come. It's for our children's future… Untuk masa depan anak-anak kita…"