IT'S slow-moving but time flies. It's meditative and weirdly exhausting. I'm trailing after nature guide Steven Wong Siew Por and trying hard not to trip over exposed roots and loose rocks on this undulating trail into the forest.

Everything is pitch dark, and only illuminated by the lamps on our headbands. I can feel cold sweat trickling down the back of my neck as I find myself surrounded by a cacophony of frog calls.

The atmosphere teems with a muggy humidity, a stark reminder of the rain that has just passed. In this thick, moist air, the night comes alive with the vibrant calls of frogs and toads, converging in their nocturnal breeding grounds — each call a testament to the pulsating life that thrives under the cloak of darkness.

"You hear that?" Wong asks. Not waiting for an answer, he continues: "The Krikkkk…. krrickkkk… kricckkk… that's the Darkside narrowmouth frog (Microhyla heymonsi). Then, there's this uwweyyyk… uweyyk… uweykkk… that's the Mukhlesur's narrowmouth frog (Microhyla mukhlesuri). Every now and then you'd hear a wekkkk… wekkk… wekkk… that's Four-lined tree frog (Polypedates leucomystax)."

I'm trying to jot in my notebook the sounds he makes, but in all honesty, it's like trying to decipher an all-frog choir without a programme. Everything out here blends into a ribbiting symphony, and I'm just here pretending I can tell one frog's song from another's.

Wong promises I'll be able to see frogs out here in this little forest enclave right smack in the middle of Shah Alam, Selangor. It's hard to imagine I'm here at the Shah Alam Community Forest, located between Setia Alam (Section U13), Alam Budiman (Section U10) and NusaRhu (Section U10).

His words are almost drowned out by the roar of a passing motorcycle, briefly pulling us back to the urban edges we're teetering on. It's a vivid reminder that we're just a stone's throw from the city. But the sounds of crickets and frog calls amidst whispering trees and the rustling of shrubs in the slight breeze tell us that a different world hovers here just waiting to be explored.

Just moments earlier, I was in a cafe, latte in hand, discussing my lifelong aversion to frogs with Wong, a nature guide and herping enthusiast. "I hope to change your mind about frogs," he tells me, smiling.

FROGS AND TOADS

World Frog Day on March 20 had slipped by unnoticed, with few pondering the humble amphibian. But who really thinks about frogs and toads anyway?

With their bulbous eyes, webbed feet and penchant for hopping, these creatures that lurk on water's edges and perhaps even in the corners of your garden have hopped their way into myths, folklore, proverbs and fairytales across cultures for centuries. We've all heard about smooching a frog to find a prince or watched Disney's Princess and the Frog for a ribbiting twist on that old tale.

For 200 million years, frogs and toads have been the resilient residents of Earth, thriving in an ever-changing world. "They're about as old as dinosaurs!" I exclaim and Wong laughs. These ancient amphibians, belonging to the Anura order, are a living bridge to the distant past and a testament to the wonders of evolution.

According to the Frogs & Toads of Malaysia: Malaysia Biodiversity Information System (MyBIS), Malaysia boasts an impressive 254 species of frogs and toads, predominantly inhabiting rainforests and wetlands.

Peninsular Malaysia hosts 111 species, while Sabah and Sarawak are home to 182 species, with 39 species found in both in the Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah and Sarawak. There are a number of endemic species, some unique to the peninsula, others to Sabah and Sarawak.

An endemic species is unique to a specific region, thriving only there thanks to unique geographical or ecological conditions. Such species serve as markers of a region's distinct biodiversity and ecological character.

"The wealth of frogs and toad species is a testament to Malaysia's rich biodiversity," shares Wong. Malaysia is recognised as one of the 17 megadiverse countries globally, celebrated for its rich biodiversity. This group of countries together hosts nearly 70 per cent of the world's known species, highlighting our nation's significant contribution to global biodiversity.

The 34-year-old is brimming with enthusiasm to share his knowledge, quickly pulling up a presentation on his laptop. The images he shows me are stunning, a testament to another of Wong's passions: macrophotography.

The frogs' translucent-like skin glints in the soft light while their large eyes, webbed feet and distinctive characteristics have an unexpected beauty to them. "They're beautiful!" I blurt out and he nods, remarking: "See? I told you frogs are cool!"

At first glance, it's easy to underestimate the significance of frogs and toads, yet they're essential to our ecosystems.

Frogs possess an extraordinary yet vulnerable feature: their skin is permeable, enabling them to absorb oxygen directly from their surroundings. However, this unique trait also makes them susceptible to harmful toxins present in their environment. Because of their sensitivity, frogs often serve as early indicators of environmental stress, such as pollution or the misuse of pesticides in their habitats.

"They're like the canaries in the coal mine," he says, referring to an early warning system used historically in coal mining. Miners used caged canaries in coal mines as early warning signals for toxic gas leaks, like methane and carbon monoxide, because canaries are more sensitive to these gases. If a canary showed distress or died, it alerted miners to evacuate before the gas levels became dangerous to humans.

This heightened sensitivity contributes to a significant decline in amphibian populations globally, with one out of every three amphibians facing the threat of extinction. Within the ecosystems of wetlands, amphibians are crucial for maintaining ecological equilibrium.

They also play a dual role as both predators and prey. By consuming insects, they help regulate pest populations, and as a food source for larger animals, they're integral to the food chain.

The decline of amphibians, therefore, not only signals a loss of biodiversity but also disrupts the delicate balance necessary for healthy ecosystems to function. I'm sure that somewhere along the line, a dedicated science teacher tried her best to teach me all of this, but I probably tuned her out!

LOVE FOR NOCTURNAL ANIMALS

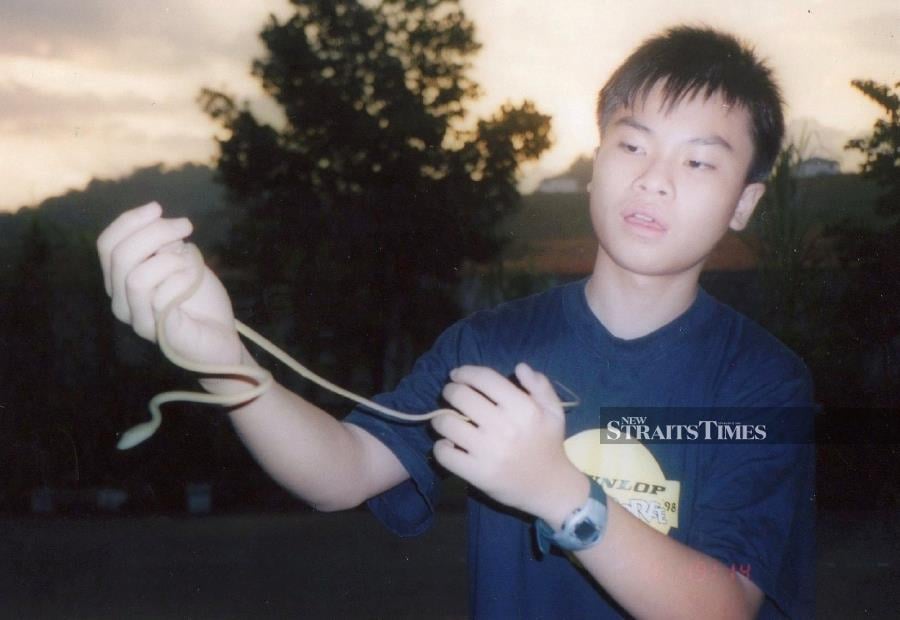

"I actually love snakes!" confesses the Cheras native sheepishly. His fascination began at age 5, right after his mum brought home the family's first computer. Included with the purchase was a bundle of free software, one of which was Microsoft's Dangerous Creatures.

"Think of it as a kid-friendly version of Wikipedia, filled with pictures," he explains. This software introduced him to a world of formidable animals, including tigers, bears and notably, snakes. "To this day, I vividly remember being captivated by a beautiful picture of the Yellow eyelash pit viper (Bothriechis schlegelii) from Central America. You can say it was love at first sight!"

With another grin, he remarks drolly: "Snakes are cool too!" and we laugh heartily.

By the time Wong was 8, his idol was none other than the late Steve Irwin, famously known as "The Crocodile Hunter". Irwin wasn't just an Australian zookeeper but also a passionate conservationist, television star, and educator on wildlife and environmental conservation. "I loved his documentaries," Wong says wistfully, acknowledging that Irwin's untimely death hit him hard. "He was definitely a major influence on me."

There were plenty of encounters with snakes, frogs and toads over the years. "I remember catching frogs and toads when I was a child," he recalls. During a family camping trip in Karak, Wong encountered a Malayan krait (Bungarus candidus), a venomous snake, gliding through a swift stream. In a bold move, he attempted to catch it, only to be held back by his uncle. Looking back, Wong laughs: "On hindsight, that was probably a good thing I didn't catch it!"

Another time, Wong encountered some Oriental vine snakes (Ahaetulla prasina) near his father's vegetable patch. "My first experience handling a snake was with one of those," he shares.

Wong's passion for these creatures initially steered him towards a dream of studying zoology. However, his parents nudged him towards environmental science, suggesting it offered broader career opportunities.

Heeding their advice, he pursued this field at Monash University. It was at university that the then 20-year-old Wong began herping in earnest after attending the Tropical Terrestrial Biology field course.

Herping, the hobby of spotting reptiles and amphibians, comes from "herpetology", which is just a fancy word for studying these cold-blooded critters. While bird watchers get the sleek title of "birders", those of us who geek out over snakes and frogs are called "herpers". Sure, it might raise a few eyebrows because it sounds suspiciously like a certain STD, but hey, it's all in the name of science!

"Herping is an easy hobby to get into," the bespectacled man insists, adding: "…because it requires little to no equipment and you can do it anywhere — from your own backyard to the heart of a forest and everywhere in between."

After some years as an environmental consultant, Wong merged his university-sparked passion for photography with his lifelong love for herping. He joined Nature Inspired, a Malaysian ecotourism provider that specialises in wildlife and cultural tours across Southeast Asia, finally aligning his career with his passions.

Since then, there's been no turning back.

UNFORGETABLE NIGHT WALK

"There it is!" Wong exclaims, directing his laser light towards a dense patch of shrubs by a stream. "That's a Common grass frog (Fejervarya limnocharis) right there."

I squint into the darkness, unable to catch a glimpse of the minuscule frog. It's truly remarkable how he can detect such hidden life under the veil of night, illuminated solely by our headlamps. Spotting these camouflaged beings, blending seamlessly with the rocks and grass by the stream, undoubtedly takes years of experience.

"The call of the Common grass frog is quite unique… katakatakatakatakatak. Some believe that the word katak, which means frog in Malay, actually comes from this sound, Wong explains, positioning his camera for the perfect shot.

How on earth does he manage to sight these frogs? "Eye shine and body shape," he replies, adding: "As a hobbyist, you'll also learn about their habitats and where they're most likely to be found. It takes a bit of practice but it's really not difficult to find them."

Wong shows me the proper way to handle the torchlight. "Hold it close to your dominant eye and direct the beam along your line of sight to spot the reflective eye shine," he instructs, demonstrating the technique.

Frogs are in abundance tonight, after the evening rain. We spot the Four-lined tree frog, the Darkside narrowmouth frog and the Crab-eating frog (Fejervarya cancrivora).

There's something innately magical about walking into the dark forest, guided by frog calls and eye shine. Nocturnal creatures move in the shadows, frogs and toads vocalise in a mix of courtship and territorial assertion, while the underbrush rustles mysteriously.

Above, a Large-tailed nightjar (Caprimulgus macrurus) takes flight, a fleeting shadow against the night sky. Along our path, we encounter the graceful Tropical swallowtail moth (Lyssa jampa) and stumble upon an Abandoned-web orb-weaver spider (Parawixia dehaani) crafting its intricate web. The night, it turns out, is teeming with life waiting to be discovered.

From afar, a pair of Lesser mousedeers (Tragulus kanchil) cautiously watches us, their presence a reminder of the wilderness so close to urban life. "There are tapirs around here too," Wong mentions softly.

The area of secondary lowland forest we're exploring acts as a critical ecological corridor linking two larger forested areas: Bukit Cherakah Forest Reserve and Taman Botani Negara Shah Alam.

Despite being encircled by development, this patch harbours a rich biodiversity, showcasing nature's resilience and the importance of conservation efforts in maintaining these green bridges between habitats.

As our journey through the night comes to a close, Wong turns to me with a smile. "Hope you enjoyed the herping session," he says, adding: "Maybe it could turn into a new hobby for you."

Maybe it could.

The once alien chorus of frogs now carries a hint of familiarity, even camaraderie. Perhaps it's time we lend an ear to their nightly serenades, recognising the tales they tell of survival, of their importance to our ecosystems, and inadvertently, to our own lives. It's a reminder, subtle yet profound, of the interconnectedness of all living things.

And the best part? My perspective shifted without having to resort to kissing a frog!

For more of nature tours off the beaten track (and herping), visit www.natureinspired.asia.