IN late December 1910, a 31-year-old doctor, hailed as one of the brightest minds of the time, arrived in the Chinese city of Harbin, Manchuria, where winter showed no mercy with its relentless harsh grip.

Following his graduation from Cambridge University in 1902, the man had honed his skills in bacteriology under the esteemed guidance of Professor Karl Fraenkel at the University of Halle, Germany, and later under the tutelage of Professor Elie Metchnikoff at the renowned Institut Pasteur in Paris, France.

Accompanied solely by an assistant, believed to have been a senior student during his days at the Army Medical College, he was confronted with the grim reality of many falling prey to the mysterious malady sweeping through the densely populated Fuchiatien, an integral part of the Harbin territory.

Upon his arrival, he was shocked to discover the absence of hospitals, laboratories and even rudimentary healthcare facilities.

The city was in the suffocating grasp of fear, its inhabitants gripped by dread. Yet, undeterred by the grim spectacle, this courageous soul pressed forward.

Unclaimed bodies were strewn across squalid streets as the biting sub-zero temperatures forced the living to seek refuge in cramped confines of dilapidated dwellings.

LOOMING SPECTRE

The primary culprit under scrutiny was bubonic plague, initially believed to propagate through the bite of fleas from infected rats — a hypothesis put forward by Russian medics.

Panic swiftly descended upon the international community, with the city's accessibility via railways from Russia and neighbouring countries exacerbating the sense of urgency. Fearing for their lives, many residents hastily fled, unwittingly bringing with them whatever it was that was responsible for the catastrophic loss of life.

With the looming spectre of unchecked escalation, there was a fear that foreign entities might intervene by deploying their own teams to address the crisis. This juncture was pivotal, casting a shadow of uncertainty over the political landscape in Peking as leaders grappled fruitlessly with devising an effective solution.

EYE OF THE STORM

Thus, the young gentleman, plucked from relative obscurity by Grand Councillor Yuan Shih-Kai to serve as vice-director of the Imperial Army Medical College in Tientsin, found himself thrust into the heart of the maelstrom.

Having endured unjust treatment in his native land due to his staunch advocacy against the scourge of opium addiction, he now faced the Herculean task of swiftly quelling the escalating panic in Harbin.

Older than Einstein by just four days, his main objective upon arriving at the epicentre of the outbreak was to identify the cause of the devastating plague. To achieve this, he urgently needed to perform comprehensive post-mortem on the bodies of afflicted individuals.

Due to deeply entrenched cultural beliefs that had endured for generations, he was consistently denied permission by the families to conduct his crucial autopsies.

His breakthrough moment came when a Chinese innkeeper, grieving the loss of his Japanese wife to the mysterious illness, granted him permission to examine her body.

Upon analysis, he discovered traces of Yersinia pestis bacterium, leading him to conclusively diagnose the outbreak as pneumonic plague. This bacterial strain posed a grave threat as it could be transmitted through air droplets when infected individuals coughed or sneezed, unwittingly exposing those in close proximity to the deadly pathogen.

NEWFOUND KNOWLEDGE

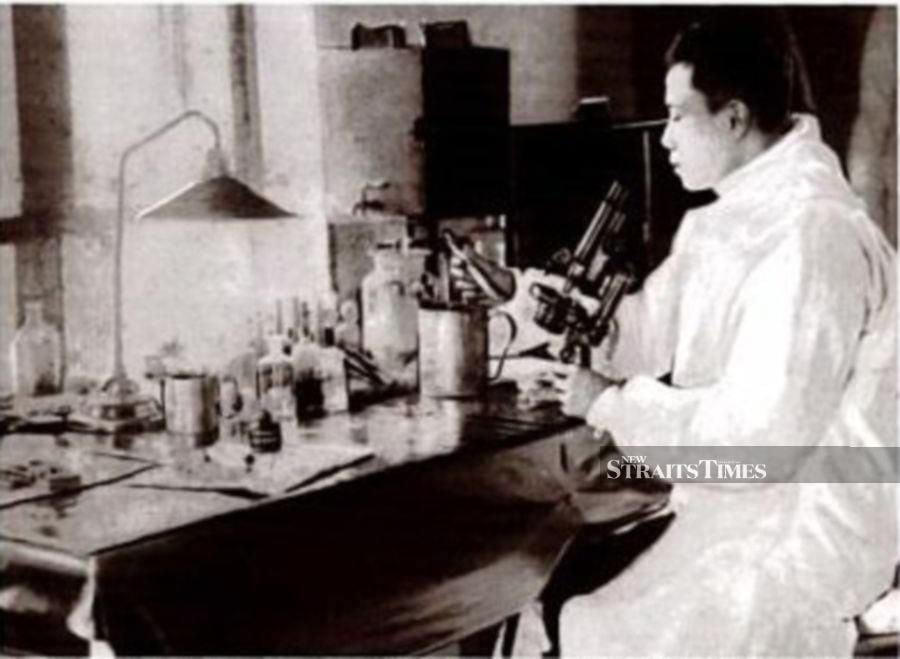

His makeshift laboratory comprised nothing more than a rundown hut constructed from mud and straw, its sole source of warmth a towering wooden stove. Fortunately, the microscope relied on electricity for illumination.

Despite the lack of modern amenities like incubators, he persisted in cultivating bacterium cultures at room temperature. Undeterred by the humble surroundings, his focus remained fixed on achieving results.

Empowered by this newfound knowledge, he fervently advocated for all hospital staff to shield their noses and mouths with clean gauze and cotton wool — a traditional face mask which, although uncomfortable to wear, became a vital tool to prevent the airborne bacterium from infecting its wearer.

Yet, his innovative approach encountered staunch resistance from seasoned French expert Professor Gerald Mesny, who rebuffed the directives of the younger doctor. Dismissed as unworthy, his warnings went unheeded as Mesny persisted in treating suspected patients without adopting the recommended protective measures, blatantly undermining the authority of the newcomer.

However, the tragic demise of the professor, who himself fell victim to the illness, sent shockwaves through the medical community, serving as a sobering reminder of the perilous stakes at hand.

ENTER THE MALAYSIAN

The Western-educated young Malaysian, Dr Wu Lien-teh, swiftly took charge, formulating essential strategies to contain the plague's spread. He convinced the authorities to halt outstation travel to and from afflicted Harbin, despite the looming Lunar New Year.

This measure aimed to prevent seemingly healthy yet infected individuals from carrying the deadly bacterium to their homes, potentially igniting a catastrophic disaster nationwide. To bolster enforcement, soldiers were mobilised to stop panicked individuals from trying to flee the grim reality before them.

His special face mask, a product of his ingenious mind, was advised to be worn regularly as a primary defence against airborne droplets carrying the contagion from infected individuals.

Despite initial scepticism towards this innovation, its importance became increasingly apparent. The closer the proximity to potential sources of infection, the more imperative the use of these masks became.

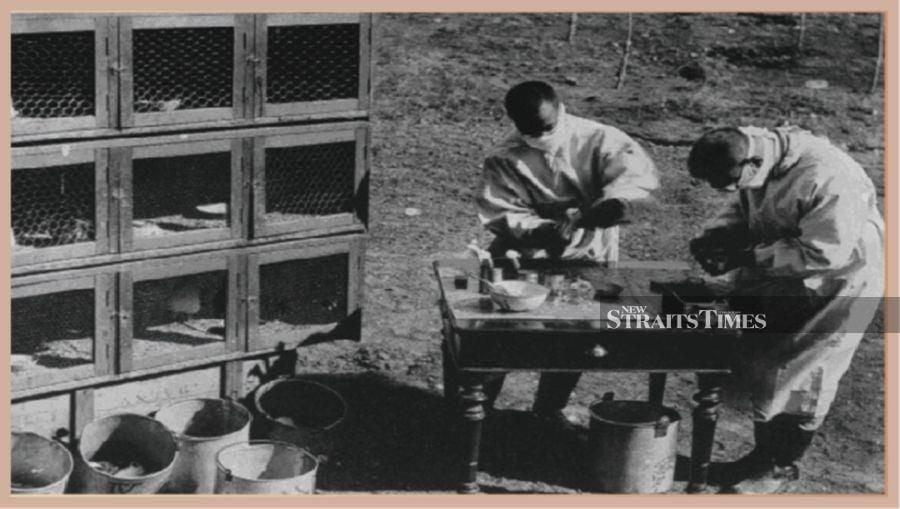

Other drastic public health measures deemed necessary included the establishment of isolation camps, where apparently healthy individuals in close contact with victims were promptly quarantined.

Horse carts were employed to collect bodies lying on the streets, yet the frozen ground posed a formidable obstacle to burial efforts. Undeterred, he swiftly petitioned the authorities in Peking for permission to expedite cremations, despite vehement protests from residents.

MONUMENTAL CONTRIBUTION

By March 1, 1911, the efficacy of these drastic measures became evident. No new cases were reported, enabling Dr Wu to redirect his attention to neighbouring towns. By the end of April, the plague was believed to have been halted in its tracks through these effective countermeasures.

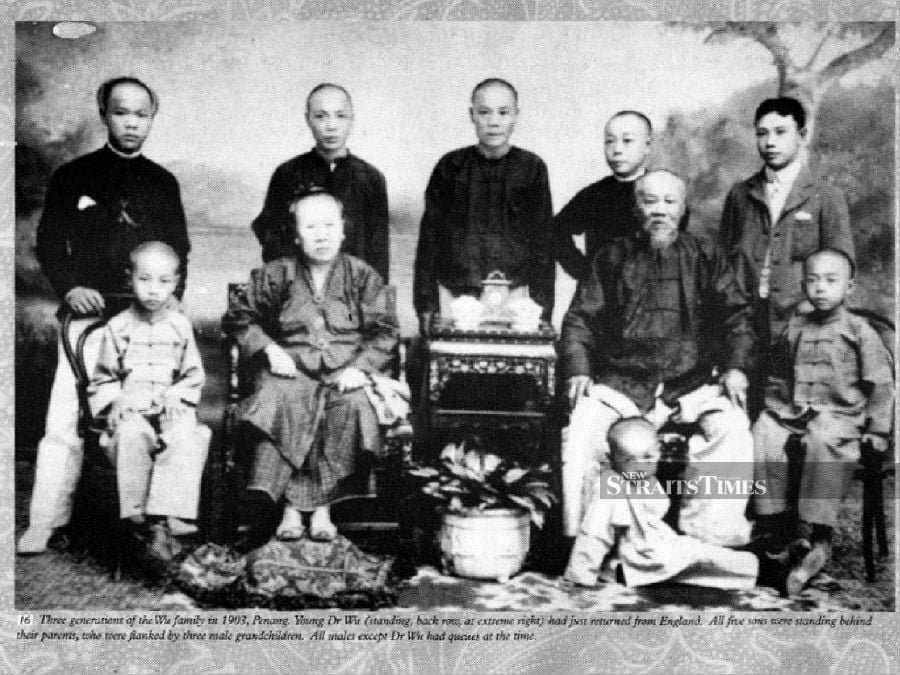

Dr Wu, a former student of Penang Free School, emerged as the first and only Malaysian to be nominated for the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1935, owing to his monumental contributions to the global medical community.

On his 142nd birthday on March 10, 2021, at the height of the pandemic gripping the world, Google Doodle took the liberty to honour him for being the first to invent the surgical face mask, widely considered to be the precursor to the N95 mask of today.

Tan Bok Hooi is an entrepreneur focused in healthcare consultancy and talent acquisition. A former student of Penang Free School, Tan was a member of the Wu Lien-teh (green house) sports house. He is also the author of six books in Malay and English, and he can be reached at [email protected].