"THERE has got to be an easier way than this!" I mutter to myself. Afternoons are never a good time to go circling around PJ New Town and hoping for a miracle of sorts to materialise in the form of an empty parking lot. Three rounds and I'm beginning to grit my teeth.

It's frustrating. Because the Ingenieur Building where I'm headed is… Just. Right. There. So near but I can't get to the darned building on account of my car. Every time I pass it, I let out a sigh. My phone suddenly pings with a WhatsApp message. "Am in my office," the message reads. Great. Now I'm officially late for my appointment.

Few rounds and many sighs later, a parking space appears like a mirage in the blazing heatwave. Thanking the heavens above, my car is duly parked and I do a slow jog towards the building.

The blast of cold air that greets me as I step out of the lift is a welcome change from the stifling afternoon heat outside. I'm finally here at the Institution of Engineers Malaysia (IEM).

The largest professional organisation in the country, IEM brings together engineers of all disciplines across the nation and aims to promote, as well as advance the science and profession of engineering and to facilitate the exchange of information and ideas related to engineering.

Don't be fooled by the humble, nondescript building here in Petaling Jaya. Engineers rule the world. Don't believe me? Take a dramatic example. In Apollo 13, the movie is as much about engineering as it is about adventure. Three astronauts are slowly dying in their spacecraft's toxic internal atmosphere, loaded with carbon dioxide.

Back in Houston, a nerdy Nasa engineer spills a carton of hoses, duct tape and whatnots on a table. Technicians — a half-dozen bespectacled men in white short-sleeve shirts — are told to make a CO2 filter.

The table holds what the astronauts have in space. The guys make the filter. The astronauts duplicate the filter, following Houston's instructions. The filter works. The astronauts live. If engineers can't save the day (and the astronauts), tell me who can?

The IEM serves as a bastion for today's real world-solvers and if that feels like a man's job to you, think again. A woman sits at its helm today, and judging from the number of women hard at work in this surprisingly spacious office, it doesn't appear to be a club of sorts for male engineers; men with their Ir titles which stands for ingenieur — derived from the Latin words for "to contrive" and "cleverness".

To gain that "Ir" status in this complex field, you need to complete your education, register as a new engineer, complete three years of professional experience and pass an examination proving you have attained the expertise necessary to handle projects or research independently — gender notwithstanding, of course. And yes, that explains the name of the building — Ingenieur — a suitable compass for the respected professional body.

It isn't a man's domain at all, insists Professor Ir Dr Norlida Buniyamin. Bold statement indeed, despite the fact that she has been appointed as IEM's 36th president and the first woman to head the institution in its 63-year-old history. But Norlida seems blissfully unaware of the history-making appointment. In fact, she tells me that women have long been running the "show" here at IEM for decades.

"Take a look around," she invites me, waving her hand around the bustling office. "It's the secretariat here who runs a tight ship," she declares again, before lowering her voice and continuing with a wink: "And guess what? They're all mostly women as you can see!"

WOMEN IN ENGINEERING

Surprisingly, it hasn't been difficult to take up the mantle of leadership, she says with a shrug of her shoulders. "Strong women aren't an anomaly here at the IEM. In fact, we've always had women working hard behind the scenes and running the secretariat ably for decades!" she stresses with a wide smile.

Of course, it's harder to compete out there in the field with men, she acknowledges. "Here, it's easy. I have a strong team that ably backs me up. But out there in the field, it's a lot more difficult," she explains candidly, adding: "I've been quite lucky though. Throughout my career, I've been surrounded by positive men!"

In fact, she reveals that out of the engineering class of 70 students at the University of Adelaide where she earned her degree in electrical engineering, there were only four female students. "Imagine that!" she exclaims with a shake of her head.

Historically, it's been a male-dominated field across the globe. For a while, the engineering industry has been failing to inspire young women to invest their time into forging a career as an engineer.

Secondary school education showed a startling lack of information for students about how diverse and far-reaching the opportunities are in an engineering career. The confusion around what an engineer actually is meant that a large number of female students weren't aware of what options are available in engineering.

Then, of course, there has been a historically ingrained gender bias. Societal traditions, says Norlida, once portrayed the engineering profession as a male-dominated field, and this was a damaging perception for aspiring female engineers to contend with. Any curiosity that arose in teenage girls was likely to end in disenchantment as the belief grew that they'd be unable to compete with boys, even in hopes of being treated as intellectual equals.

"This has got to change, of course," she remarks firmly, adding that IEM is in the midst of a study to determine the actual percentage of women in the entire engineering workforce in Malaysia. IEM's membership, she reveals, shows that women engineers make up only 20 per cent of their vast database.

"We need more women engineers out in the field!" she declares. The timing, she adds, has never been better for women to begin training in engineering and the career prospects are very promising as companies will be incentivised to populate their workforce with women and a more-diverse range of professionals.

"It's not an easy profession," she admits. "But engineering is a fascinating and ever-evolving subject. There are many specialities to choose from according to your interests, as well as a huge range of jobs available. As an engineer, you can make your mark on the world in a positive and enduring way."

ACCIDENTAL OCCUPATION

But she's surprisingly blasé about her own journey into the field. There was no higher calling, she admits, her eyes twinkling. "I simply wanted to go overseas lah! I had a scholarship, so I applied and got in!" reveals Norlida with hearty laugh.

Born in Terengganu to a policeman father and a mother who was a teacher at the Methodist Girls' School in Kuala Lumpur, Norlida is the youngest of seven. "Within the family, there are architects, teachers, doctors and engineers. Surprisingly, none of the younger generation wants to follow the traditional doctor-lawyer-engineer route!" she says half-wistfully.

The amiable 59-year-old confesses that her childhood ambition was to become a vet. Growing up in Kuala Lumpur, Norlida and her siblings lived in a bungalow with a big garden where they cared for many animals that found their way into the compound. "We had cats, rabbits… even a civet cat!" she recalls, grinning.

Still, there was shadow that fell on their family when her father passed away when she was 7. "My mother took care of the family," she tells me, adding: "We weren't well off, but we got by despite the circumstances because we had a lot of family support."

After studying at MGS, Norlida continued her studies at boarding school, where she excelled in sports, which included hockey, volleyball and basketball. "I love sports!" she exclaims, before adding regretfully: "Not that I look like that I'm sporty anymore. It's been a while since I've been out there playing sports. I miss those days. I've put on so much weight now after my knee operation!"

Forget about getting her "engineering" passions stoked after entering university — she was too busy enjoying the outdoorsy Australian state. "I mean, I wasn't an 'A' student but I did pass all my exams lah!" she protests with a grin.

Still, she enjoyed her stay in Adelaide. The young university student spent her time skiing, skating, hiking, shooting and orienteering when she wasn't compelled to hit the books and pass her examinations. "I had the best times there. I only wish I stayed a little longer in Adelaide!" she shares.

Norlida spent her first summer teaching mathematics at a primary school out in the outback, the colloquial name for the vast, unpopulated and mainly arid areas that comprise Australia's interior and remote coasts. "I love the idea of giving back," she explains simply. "And teaching brought that satisfaction for me."

She returned to train at Tenaga Nasional Bhd (TNB) in her second year, and for her third year, Norlida trained at JKR (Public Works Department). She graduated soon after and returned home with an engineering degree.

WOMAN ENGINEER

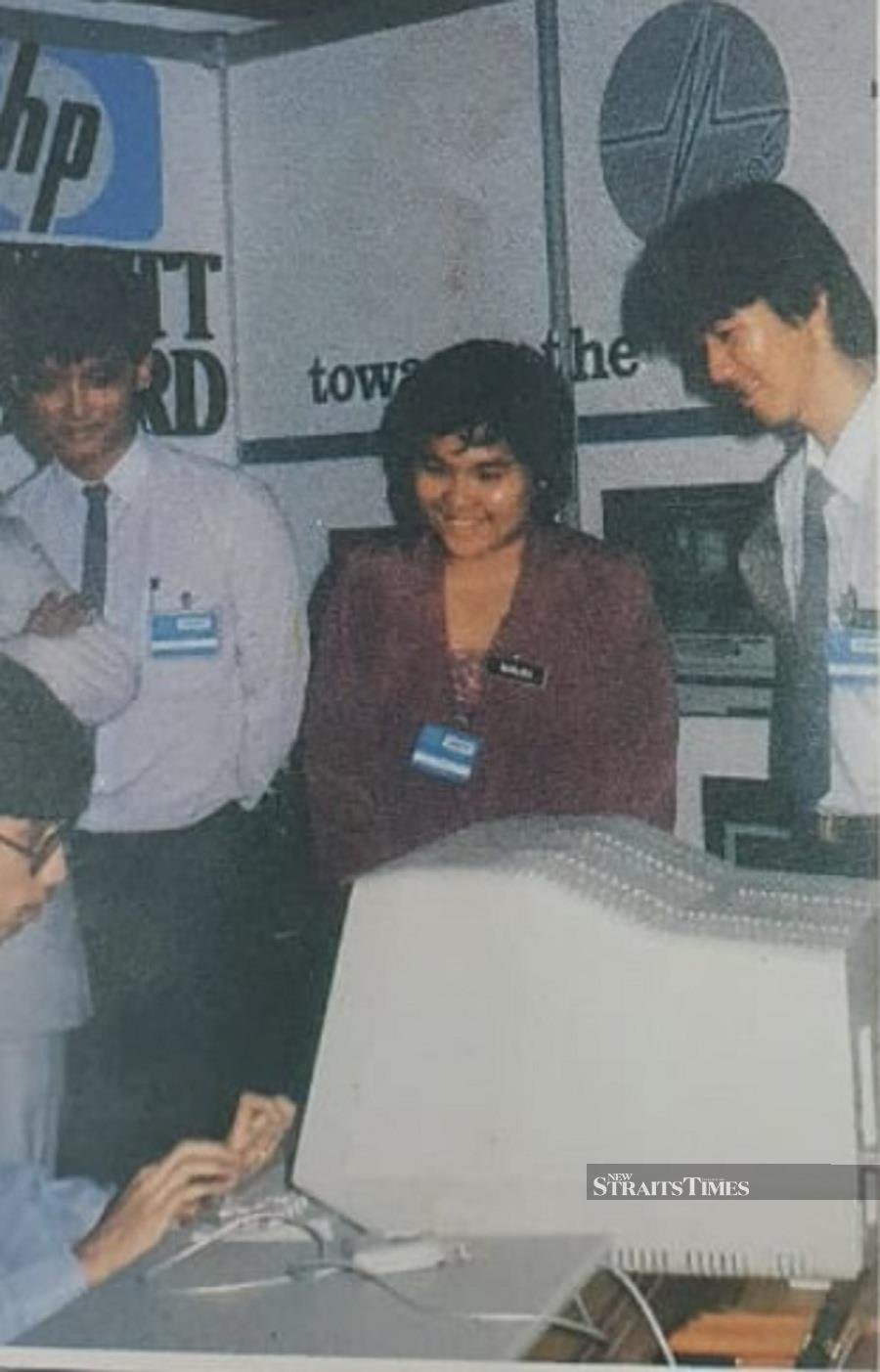

"I was very lucky," she declares again. The young graduate returned at the worst possible time — the recession in Malaysia during the 1980s had reached its peak. Norlida managed to work in what was then known as Malaysian Institute of Microelectronic Systems (Mimos), now Mimos Bhd, Malaysia's national applied research and development centre under the Science, Technology and Innovation Ministry.

"I designed the first digital chip at Mimos," she tells me, pride lacing through her voice. "I was very lucky," she repeats again. "…to receive invaluable training at Mimos. I learnt under the best engineers in Malaysia".

I'm curious to find out if she faced any gender bias while working in Malaysia. "Was it a challenge to work in a male dominated industry?" I ask her and her brows furrow as she thinks for a while.

"Not really," she replies slowly. "I think I'm pretty used to dealing with men. You must remember that I was one of the few women studying back then in a class of 70. We usually spent our time hanging out with the guys and watching football!"

In fact, she tells me that women engineers here are treated a lot better than their counterparts overseas. "When I was doing my PhD at Ford Motors, I was treated the same as any other man and given the same back-breaking and dirty tasks to complete. Here, it's different. Women are treated differently. We get the nicer desks, given the nearest parking bay to the office, and allowed to go home earlier after work!" she continues, before adding dryly: "But of course, it also meant that we were usually passed over for promotions!"

Does that mean the glass ceiling still exists in the profession? "Of course!" is her sharp rejoinder. "Women have to juggle a lot of roles to this day. We can't commit as much because we have our households to run. Mothers, wives, we have to juggle career, marriage and household. It's tough but women are certainly more than capable in giving their best to this industry. We just have to break the myth that we can't do a job as well as the guys!"

But there's a certain skein of truth about commitment where Norlida is concerned. "Take me, for example," she offers with a wide grin, admitting: "I couldn't commit 100 per cent when I was studying because I was busy having too much fun. When I started working, I refused to commit more time to my job because I wanted to have a life!"

EMBRACING LIFE

She decided that she'd had enough at Mimos and decided to venture into teaching. "I tried consulting for a while, but I disliked the long hours that came with it. That certainly wasn't for me. My brother-in-law, on the other hand, is a consultant engineer and he literally works to death. I can't imagine doing the same thing. I want to do the things I like — teaching, researching… those sorts of things!" says Norlida.

Her family and friends were aghast at her decision to venture into teaching, but she went ahead anyway. "Money may be less but I wasn't going to kill myself earning it!" she remarks staunchly.

She has a different philosophy instead. "Work hard and play hard!" she remarks blithely, breaking into a hearty laugh. Her sunny effervescence is contagious, I realise as I join her in laughter.

She tells me she received two lecturing offers from Universiti Malaya and Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Shah Alam. Her uncle, who was one of the first professors at UiTM, urged her to join his place of work. "Go where you're needed," he advised her. And so she did. "He was right," she says, adding: "Our students may not be the cream of the crop, but we hope that by the time we're through with them, they can be one of the best."

She simply wants to make a difference and teaching, she tells me, certainly does that for her. "I'm still in touch with most of my ex-students," she says with pride, adding: "When the student really needs you, you find that you impact their lives in a positive way."

She thinks her late father would be proud of her choice. "I grew up seeing my father take care of people. There was always room in our house for people who needed help or shelter. My father would care for them without expecting anything in return. That was his nature," she recalls, adding thoughtfully: "I think that sense of giving back… I might have gotten that from him."

While she's committed towards mentoring and raising quality engineers in the country, Norlida insists on living her life to the fullest without being dictated by the rigueur of the profession. "I'm an engineer but I'm not defined by it," she avers firmly. Her life off the engineering "field" has been nothing short of interesting.

The bubbly IEM president is an avid rider and has been involved in the equestrian sport for years. "My sister is the first Malaysian to compete in the 160km world endurance championship!" she tells me proudly, adding: "In fact, you should interview her. She's a lot more interesting than I am!"

From managing the Sukma (Malaysian Games) equestrian team representing Wilayah Persekutuan to being a FEI (The International Federation for Equestrian Sports) qualified judge, who frequently travels to preside over championships across the globe, Norlida intends to pursue her passions for as long as she can.

"I became a judge because I came across unfair practices at equestrian shows, and I wanted to do something about it. I'm glad that FEI has implemented some of the policies I've come up with. I enjoy making a difference this way too," she says with a smile.

She enjoys travelling and has already travelled to almost 60 countries. Norlida intends to keep that tab going with her husband, who is also an engineer and enjoys travelling, besides being an avid rider himself. They have no children, but she's lucky enough to have her four nephews who live around the corner. "I'm glad to have them for the good times. We usually send them back (to their parents) when the bad times come!" she quips, grinning.

With all that you've accomplished both in and off the field, what can you not do? I tease her. "Put on make-up!" she replies with another peal of laughter. "Honestly, I don't have time for that!" she admits, throwing up her hands. "Every morning, I swim and I go riding before leaving for work. There's not much time left to spend in front of the mirror!"

What advice would you give to young women who want to enter the field of engineering? I ask her a final question. She hesitates to answer at first. "I was never ever ambitious," she admits finally, adding: "It's hard to offer advice, you know. I turned down a lot of lucrative positions because I wanted to enjoy my life fully."

But as president of IEM? I press further. She sighs and says resignedly: "I have to, don't I?" I can't help but laugh at her tone.

"Well, you have to be committed," she finally replies. "For the first five years of my working life, I was committed and nothing stood in my way. Engineering isn't an easy profession, but it's hugely rewarding in terms of job satisfaction."

Continues Norlida: "Engineers have completely changed the world we live in — from modern homes, bridges, space travel, cars and the latest mobile technology. Innovative ideas are at the heart of what engineers do and they use their knowledge to create new and exciting prospects and solve any problems that may arise.

"If you want to be in this profession, commit your time and don't be intimidated by the fact that it's largely male-dominated. Women are more than capable of becoming fine engineers!"