VENICE has just announced that it will be charging visitors for entry, backed up by a booking system of Covid-era sophistication. The global media have reported that this is a world first. That may be true of the admission charge, but it isn't for the bookings.

Makkah has had strict quotas for decades and the Saudi site managers have also just made an announcement about further refinements. The news has not been well received by all Muslims, but when a destination is as popular as this, extra vigilance will be required.

Unlike Venice, there are religious criteria for entry to the vicinity of the two Holy Cities. And then there is Covid-19. This is the first time for three years that the haj is happening as it should. The excitement reaches fever pitch at this time, with the celebration of Eid al-Adha, also known as Hari Raya Haji and Qurban.

Soon the airport carousels will be jammed with bottles of holy water. The zamzam well in Makkah is available to the millions of pilgrims who visit the city, but the Saudi government bans its sale. As a result, confusion sets in at many airports when the plastic containers show up with the luggage. When pilgrims reach home, they don't want the ungodly walking off with their water.

Before this happens, there is Eid to be observed. Although it's connected to the haj in terms of timing, this is a slightly different festival. Commemorating the Prophet Ibrahim's sacrifice of a sheep, rather than his own son, it is a reminder of God's mercy. It is certainly not a gift to pictorial artists.

Islam has a complicated relationship with figural art; the prospect of imagery showing a prophet sacrificing anything at all would be most unwelcome. Only non-believers — and some centuries-old Persian artists — would venture into this visual realm. Even the non-believers would find such a creative project distasteful, and they certainly wouldn't be observing it in Makkah.

PAINTING MAKKAH

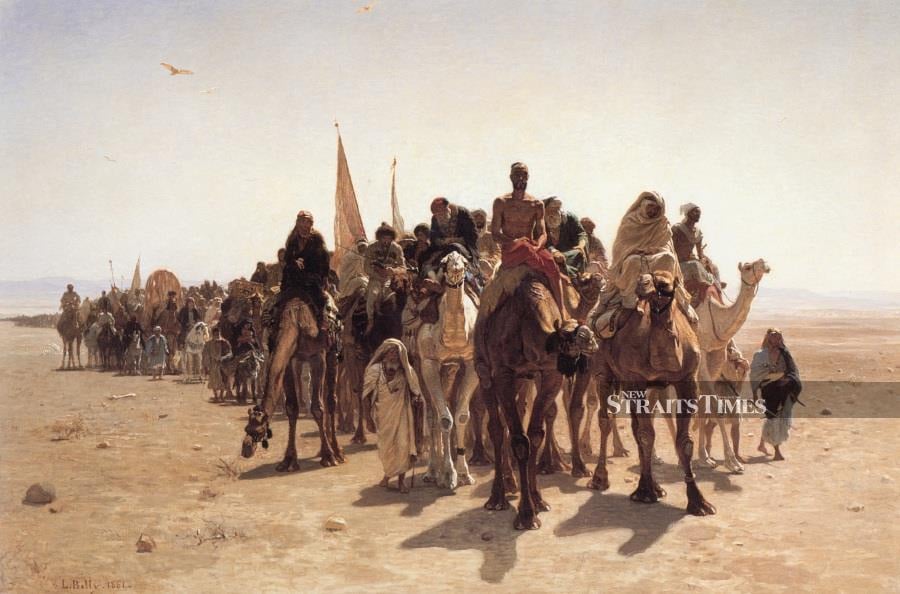

The actual journey of pilgrims from all corners of the world is another matter. Although seldom covered by Muslim artists, there have been others who were fascinated by the sight. It was mainly during the 19th century that Western painters were able to travel easily to North Africa and the Middle East.

They depicted what they saw en route to the protected places of what is now Saudi Arabia. There are not many painted records. The few that exist were mostly by French and German artists, the most numerous of these intrepid Orientalists. Some examples exist in the collection of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia, where they will be on show in a future exhibition.

Among the artists in the collection is one Frenchman who became an Islamic scholar, as well as a pious Muslim. Unfortunately, he didn't record any part of the haj although he did paint important sites such as Al-Azhar in Cairo.

Etienne Nasreddine Dinet was well up to the physical and spiritual exertions of travelling from his new home in Algeria to the Arabian Peninsula. Painting Makkah was another matter as he had become so busy with writing theological treatises.

LITERARY INTERPRETATIONS

In the intervening century, the bureaucratic rigours of the haj have become ever greater, while the travel is easier — or was until the global pandemic. In the past, getting to Makkah was only half the challenge. Before modern transport, it was just as perilous to get home. Sometimes there were other priorities, as with the great traveller from Tangiers, Ibn Battuta.

The 14th century judge covered unprecedented distances for an individual in the Middle Ages. His journey of 70,000 miles lasted for 30 years after making his haj and included a stopover in the Malay Peninsula.

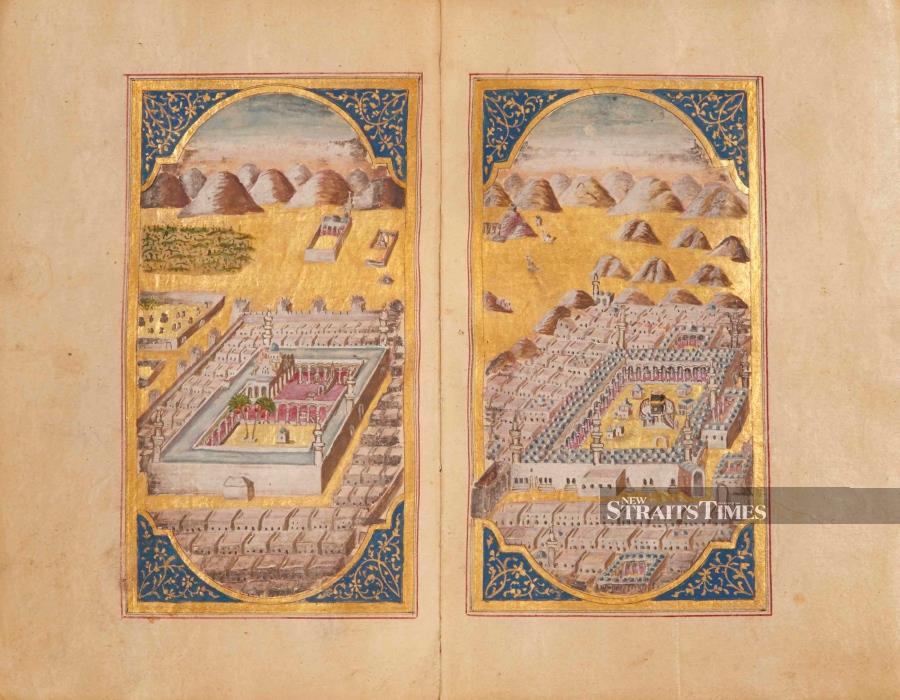

Although Ibn Battuta did a lively job describing Makkah, it is entirely literary. He mentioned details such as "clinging to the curtains of the Ka'aba", but as he never turned his hand to art, there is no visual element from him.

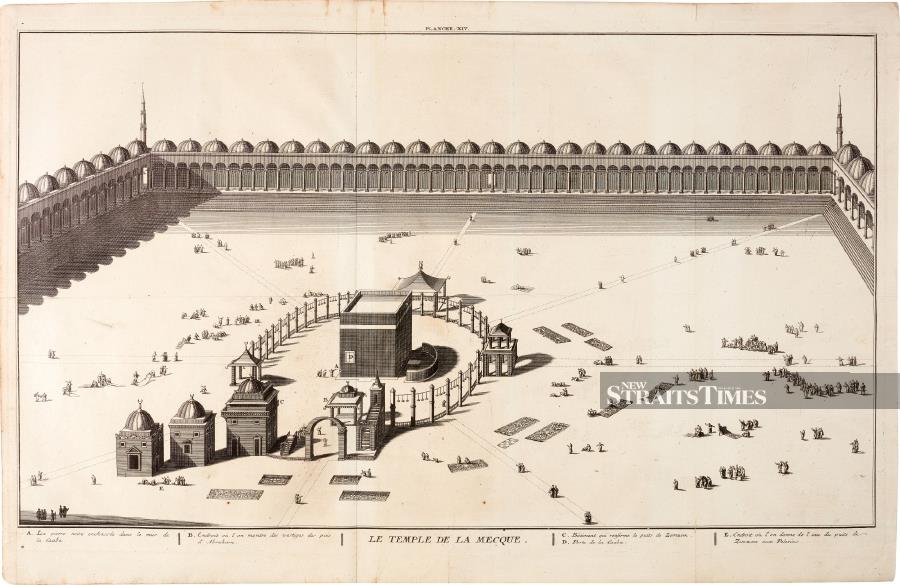

The same is true of most Muslims, except for a very small number of Persian miniatures that show the Ka'aba at about half its present mighty height, or the people in the paintings were extremely tall.

VISUAL REPRESENTATIONS

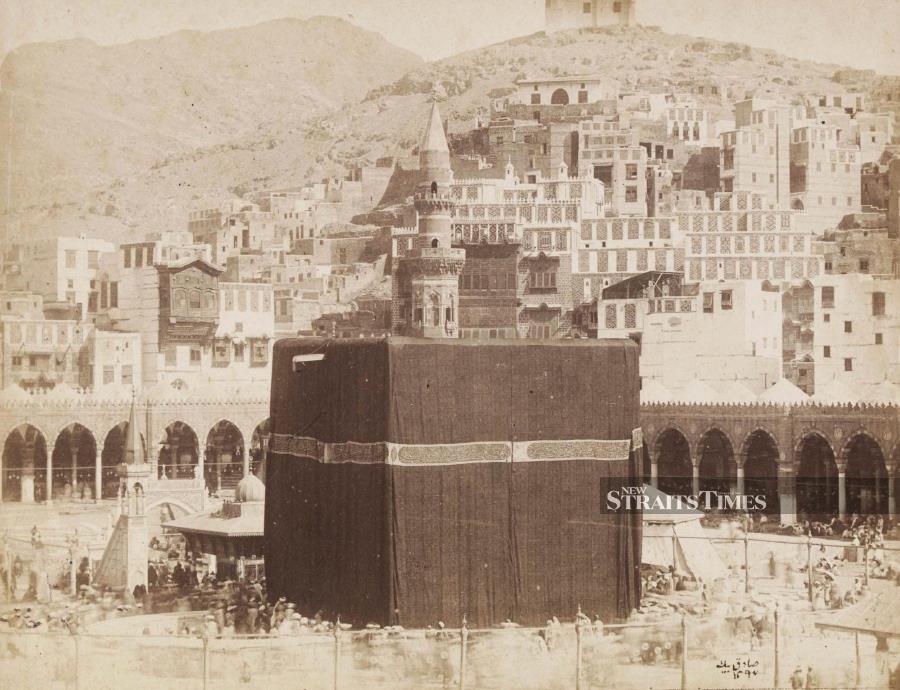

Around the middle of the 19th century, Ottoman photographers started to make up for all those missing visual representations. Among the world's pioneers was the Egyptian Sadiq Bey. He first took photos of Makkah in 1861 and then returned in 1881 to take some of the most important views of the haj ever, many within the Masjid al-Haram itself.

His work was so highly regarded in Europe, he was presented with awards such as a gold medal at the Venice Geographical Exhibition. His work wasn't just about buildings and anonymous pilgrims. There were also potentates and their entourage, including eunuchs from Sub-Saharan Africa.

These photos are important historically, but lack the drama of oil paintings, which are a riot of colour and boisterous enthusiasm. Whether on the way out or back, there was the same spiritual element that made some lively works of art. Would it have been the same if these artists had been on the haj themselves? They might have been moved by other forces than the desire to produce a highly saleable work on canvas.

Since the first haj in 629 AD, pilgrims who return tend to see themselves as changed people. After being trained from their earliest years to look forward to the journey, they often acquire a new approach to life. For the black-activist Malcolm X, it was the awakening of a new awareness of global community.

After performing the haj in 1964, he wrote: "And in the words and in the actions and the deeds of the 'white' Muslims, I felt the same sincerity that I felt among the black African Muslims of Nigeria, Sudan, and Ghana. We were truly all the same (brothers)." A powerful message six decades later.

Follow Lucien de Guise at Instagram @crossxcultural.