THE debate about cultural repatriation has been going on for a few thousand years and is not losing any steam at the moment. Usually, it's about Greece or Nigeria doing battle with Britain. Meanwhile, India has given up asking for the return of the Koh-i-Noor diamond, and Ukraine has already started to take action on Russian damage to its heritage.

Lately there has been a refinement of the subject. Human relics are now priority items. Aboriginal Australians and the indigenous populations of North and South America have been loudest in calling for their ancestors' bones to be better respected and preferably returned.

The places we hear least about for the return of any sort of artefacts tend to be in Southeast Asia. Cambodia has now entered the world-media stage. Having endured French colonialism and Khmer Rouge mass murder, they would like some of their looted past back. It's a story that is getting a lot of attention, especially in the United Kingdom and the United State. The death of the chief thief has led to the return of a huge cache of sculptures.

There have been some successes elsewhere in the region. Last year, Thailand had two Hindu stone carvings returned from the highly responsible Asian Art Museum in San Francisco.

The Thais are owed more, including objects in the matriarch of American museums, the Met.

Indonesia has also had some triumphs. Well over a thousand artefacts have been returned by one Dutch museum, mainly because it had closed for business. Not many of the items were of national significance except for a kris once owned by a heroic freedom-fighting prince from 19th-century Yogyakarta.

There's been a restrained approach from most Asean members. They haven't been ransacked quite as comprehensively as Cambodia, but there's still a lot of their barang-barang (items) in collections around the world. Some of it was returned decades ago, such as the Myanmar royal regalia.

BIGGER LOOT

In the Philippines, the big news is not the return of any objects, but rather, the return to power of a name that the rest of the world thought Filipinos couldn't possibly want. It was a convincing win for Bongbong Marcos and in that, it's possible to see some of the problems regarding the region's heritage.

All that stuff his parents ran away with to Hawaii represents the typical taste of the kleptocrat. Fashion items and jewellery were the top priority, but there was also a magnificent art collection — almost all of it paintings by predictable Western artists.

It seems they couldn't be bothered to pile their jets to the brim with traditional wares from the Philippines. They didn't really care about it, not when there were shoes to be saved. When there was an auction of the family's collection in New York in 1986, there was remarkably little with any connection to their homeland.

The rich of most Southeast Asian countries used to look at the bigger picture for loot, rather than their own parochial art. In the case of Imelda Marcos, recent photos showed that the bigger picture included a Picasso that had been lost for years — on the wall of her New York townhouse.

Similarly, colonisers and invaders from the past didn't have a feeding frenzy in much of Southeast Asia. There's certainly a huge quantity of Indonesia's finest in the Netherlands, but most of it wasn't forcibly removed in the way that African heritage was.

The French and Italians were as prone as the British to building special ships just to take away massive chunks of ancient Iraq, Egypt or Ethiopia. Wooden masks and Benin bronzes were so easy to move, they could go in hand luggage.

There is a less favourable side to the good fortune of reduced pillaging in Southeast Asia. Museums around the world often have less to look at from Malaysia and its neighbours.

There are unquestionably superb textiles from the Malay world in collections from Amsterdam to Canberra and Washington. On the whole, Malaysia and Indonesia were adept at hanging on to the best stuff and generally letting the Western imperialists get away with the second tier.

When the pride of Southeast Asian Art turns up at auction, instead of making a big noise, they are quietly bought and taken back to their homeland. Dealers and museums in Malaysia have been practising this soft cultural diplomacy ever since there was the money at home to pay for it.

China has been doing the same thing. Less of the international outrage and more about getting rich people to do their patriotic duty and repatriate with the power of the Renminbi.

LURE OF SCULPTURES

The most outrageous situation is when a piece of looted art is bought legitimately on the open market and then has an export licence denied. The British government is the worst offender.

After the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia acquired a hunting gun taken from a South Indian Muslim ruler, it was decided by Whitehall that this souvenir must be kept in the UK.

Many of the highlights of Britain's museums were, of course, obtained in the most dubious circumstances. The Parthenon Marbles are perhaps the least brazen example. The people of Easter Island are gunning for the return of a showpiece stone statue that was grabbed by 19th-century opportunists and given to Queen Victoria.

The Egyptian government has been trying for years to get back the British Museum's most popular attraction, the Rosetta Stone. To be fair to the Brits, this was stolen by the French first.

The common factor with so many items in question is that they are sculptures, usually in stone. Perhaps Southeast Asia is fortunate not to have had an excess of these, especially in the areas that followed Islam.

Cambodia and Java were the main exceptions. Phnom Penh is now actively pursuing the countless prizes hacked away from Angkor Wat and other temples. Jakarta, on the other hand, is not pursuing the stolen bits of Borobudur too vigorously. A lot of Buddhist sculptures were officially given to Thailand in the 19th century, which complicates their return.

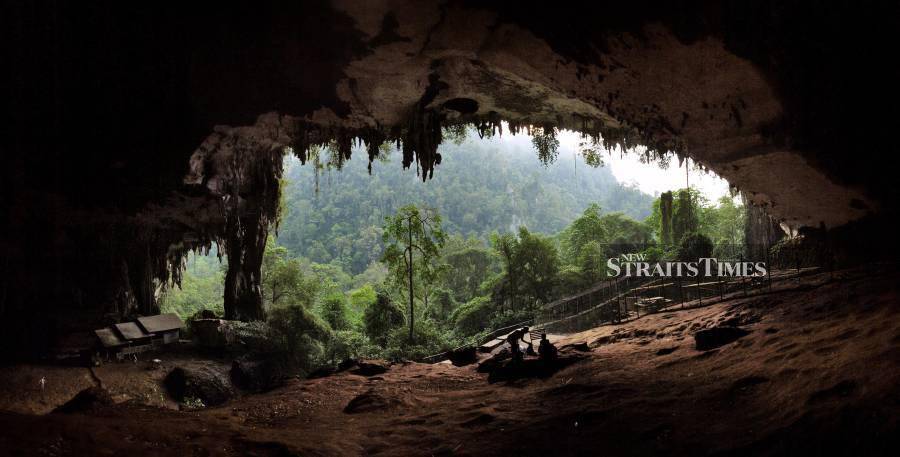

Malaysia's main initiative at the moment is human specimens taken from Sarawak's Niah Caves in the 1960s. It goes to show that for this country, people do perhaps come first — even when they died 40,000 years ago!

Follow Lucien de Guise at Instagram @crossxcultural.