THERE'S a paradox inherent in the many and varied experiences of refugees. Their journeys over thousands of miles — epic quests across deserts, mountains and seas — aren't normal by any standards. But refugees themselves — for all our attempts to "other" them — are very much normal.

They're doctors, civil servants, electricians and students. People like you and me, in fact. And their stories, like thousands of others who have been displaced through war and violence, deserve to be told.

Whether they are nostalgic reveries of those who came long ago to this nation of immigrants, or the brutal nightmares of worldwide millions fleeing persecution today, memories of migration matter. Telling these stories seems more important than ever — even, and some might say especially, to children.

So don't focus on the boat. Don't show it lurching on the waves, a crush of terrified people packed elbow to ribcage, a baby crying. Don't focus on the despair and pain. Don't focus on their past — the homes they left, the loved ones lost, the bribes paid, the calculations made and agonised over.

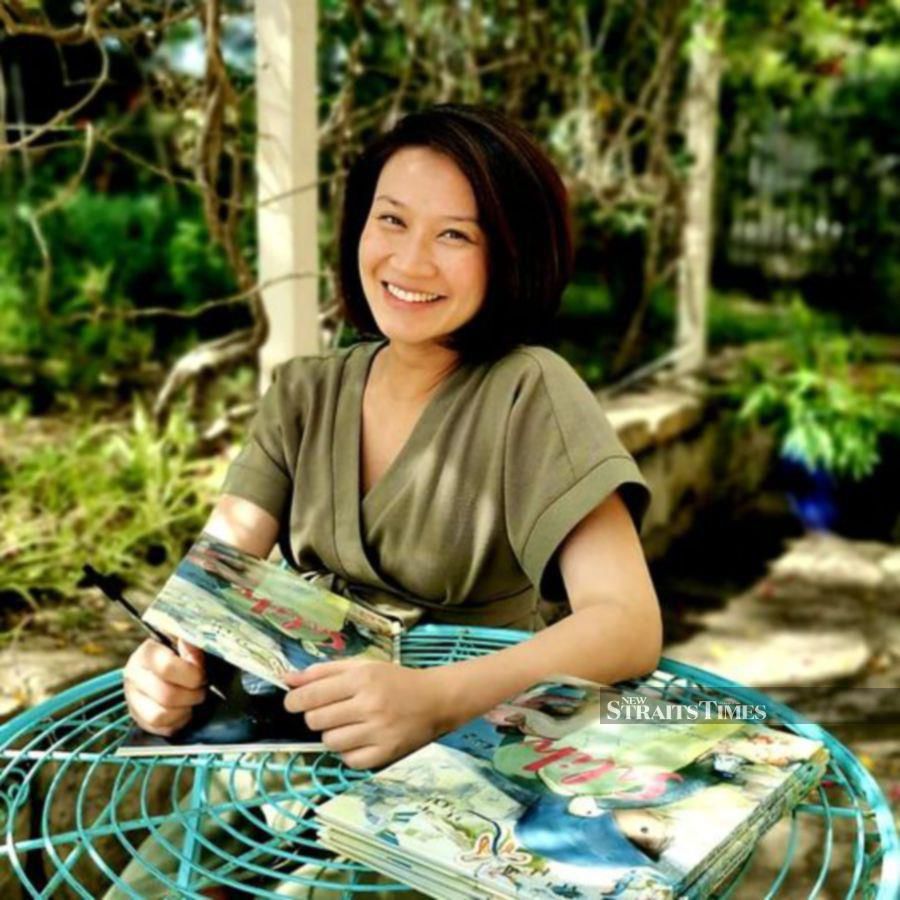

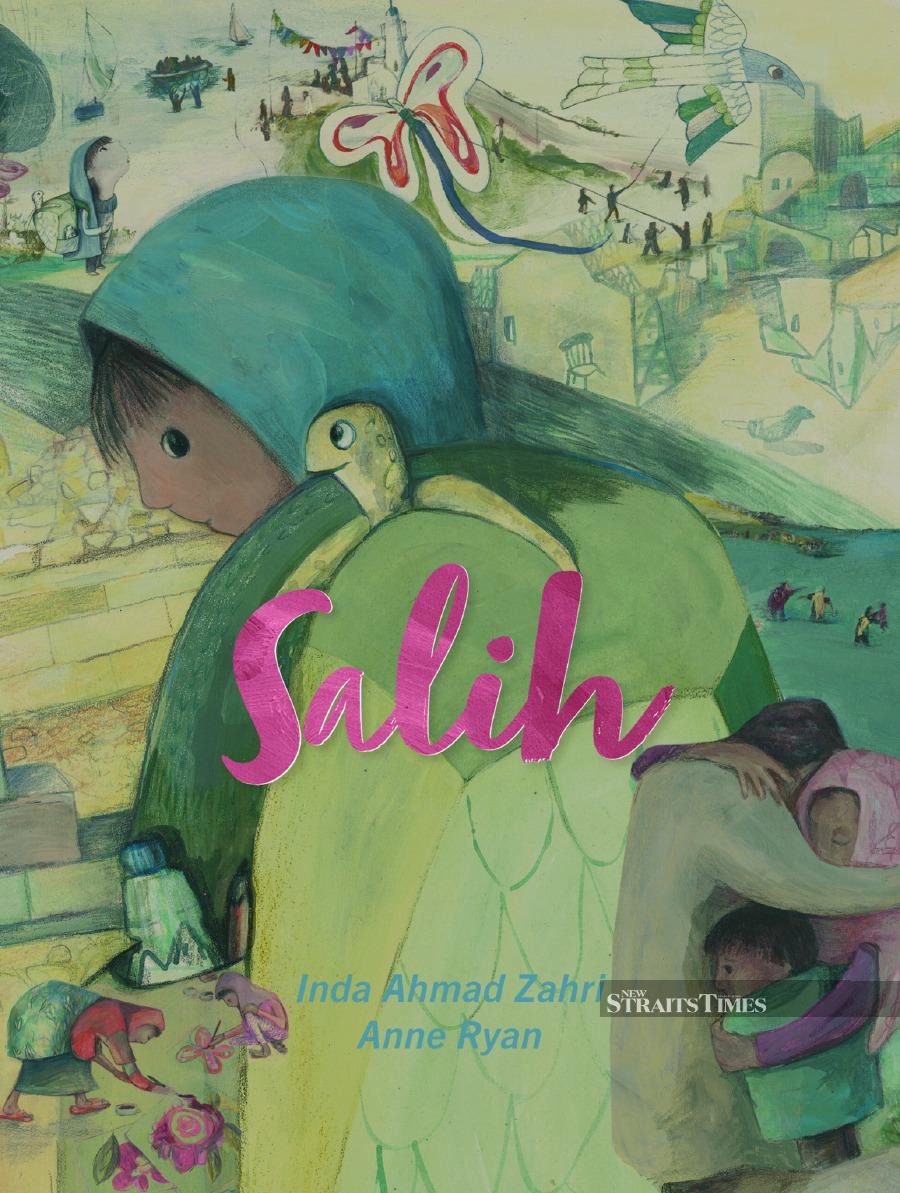

Instead, let Inda Ahmad Zahri, a 39-year-old Malaysian author, tell the poignant story of Salih, and allow her beautiful picture book to help with that monumental task.

Salih, the young boy, carries his home on his back — similar to that of a turtle, because he and his family, together with thousands of people, had fled their war-torn homes in search of a safe haven.

And Salih keeps his entire history in that one single bag. Leaving behind all that's familiar, including family and friends, Salih holds on to his memories of joyful times and cosy rituals.

"I've always been invested in the stories of refugees," declares Inda, adding: "I was trying to make sense of what was happening — firstly, for myself." The 39-year-old is speaking by Zoom from her home in Brisbane and describing her response to daily accounts of the treatment of immigrants and refugees while she was growing up in Malaysia.

"When I was a young girl, there were Bosnian refugees arriving in Malaysia who were seeking refuge away from their country. It's such a tragic thing. There are hundreds and thousands of people displaced through war and conflict, and yet, more often than not, there's no welcoming mat offered. Instead, they are treated as criminals."

She confesses to have always felt deeply about this living tragedy; about the millions of people around the world forced to leave everything they know while risking their lives to find a better place.

"When I was in medical school, I learnt even more about refugees through a group called Student Action For Refugees (STAR)," she recalls, adding: "They organised a buddy system where we would pair up with a refugee and help them better assimilate into their adopted country."

There, Inda was paired with a refugee from Iran. "She was a medical doctor, but her refugee status stripped her of everything. Here, she was battling with language problems. Her training and expertise went to waste in this new country she was in," recounts Inda.

The lack of language is a big barrier, as is a skills mismatch. Some refugees do not have the right experience, while others cannot get their professional qualifications or degrees recognised. "It opened my eyes to real issues," admits Inda.

"At the same time, I felt this responsibility to report on what was happening," she adds softly. "I wanted to boil things down to one small voice because the more personal something is, the harder it is to look away."

Around the time that she wrote Salih, there were increasing reports in the news about refugees crossing the Mediterranean from Africa or the Middle East into Europe.

"I later learned that in 2018 alone, 139,000 people arrived in Europe, though many perished along the way. What's sad is the fact that often there was no true refuge at the end of their journey. They faced prejudice, detention, persecution, and I wished so desperately for a warm welcome for them."

Adding, Inda shares: "I was a new mother, and I felt a deeper level of empathy for those who had to flee with their families. I kept wondering how it would have been to make that horrible journey with a child. It led me to imagining how this experience would be seen through the eyes of a child. How do they even survive without being traumatised?"

A pause, and she says quietly: "The images were horrific. You might have seen it on the news."

The shocking images of lifeless Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi on a Turkish beach were all over the news. As many as 12 refugees, including eight children, who sought to flee the war-torn Syria and cross the Mediterranean Sea, drowned that day. They were on a journey to reach Greek islands, but their boat capsized and all of them drowned.

The news channel Al Jazeera had snippets of news on what refugees would take along with them in their bag. "One man, a barber by profession, carried his precious tools with him. Some had their children's socks tucked away in their bag. Others had photographs or poems. It struck me then… what if I had to leave my house and all that I knew behind, and I had only one bag to carry. What would I take with me?" she muses.

What would you have taken? I ask. She shrugs her shoulders helplessly. "I don't know!" she confesses. "I love books. I've got shelves of books. What books would I choose? But at the end of the day, I think you'd have to prioritise and take the things that you need to survive, and not necessarily love. Oh, that's such a tough question!"

She named her young protagonist Salih because it meant goodness in Arabic. "That's the key message of my story anyway," she explains. "Kindness and goodness. Despite the hardship Salih and his people faced, I wanted something good to happen to them at the end."

Inda's hope, as tempered as it may be, is impressive. It is one thing to feel optimism when seated in a comfortable home in a country not quite at war, but quite another to write about people who have barely escaped unspeakable darkness, and still feel that a difference, no matter how small, must and can be made.

CHILDHOOD DREAM

It was that idealism that led Inda to pursue medicine after Form Five. "I've always wanted to save the world!" she confesses, chuckling. "You know, when you're young, you're always having that romanticised idea that you'd want to help people and make a difference."

She loved the sciences, but she also had aspirations to write. "I've always wanted to be a writer," she says half-wistfully. "But in school there was such this chasm between sciences and the arts. I found myself stuck in between. But I eventually chose the sciences!"

"I have my mother to thank for reading and writing," she tells me again. "She gave me my first book, The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole and I thought, what a brilliant idea it was to keep a diary." she recounts gaily.

Inda kept diaries growing up, and with the advent of technology, she also kept an online blog when she was in university. "I'm pretty sure my mother was my only reader!" she admits wryly, breaking into laughter.

She tells me of the "terrible" stories she wrote growing up and dreamt of writing a novel someday. She also loved travelling and as she revelled in new experiences, she was hoping for something to happen that she could turn into a great story. "But then I realised that when you're young, nothing ever interesting happens to you. You don't know anything about heartbreak or loss or even tragedy that would be worth writing about!"

Her love for writing waned as she pursued medicine and chose surgery "…because I was a little masochistic!" she quips, grinning widely. "But seriously, I chose surgery because it combined a quest for knowledge with a way to serve, to save lives, and to alleviate suffering."

The idealistic young student loved every bit of her training as a doctor. "At least until the kids came along!" she recalls, smiling. The mother of three is currently on hiatus after recently giving birth to twin boys.

"I'm taking it easy for a while now!" she chuckles. "My babies were born premature, so there was quite a bit of back and forth to the hospital for a couple of months," she explains, smiling. She's finally finding the time to write again. "I contemplated writing again when I had my eldest daughter," she reveals.

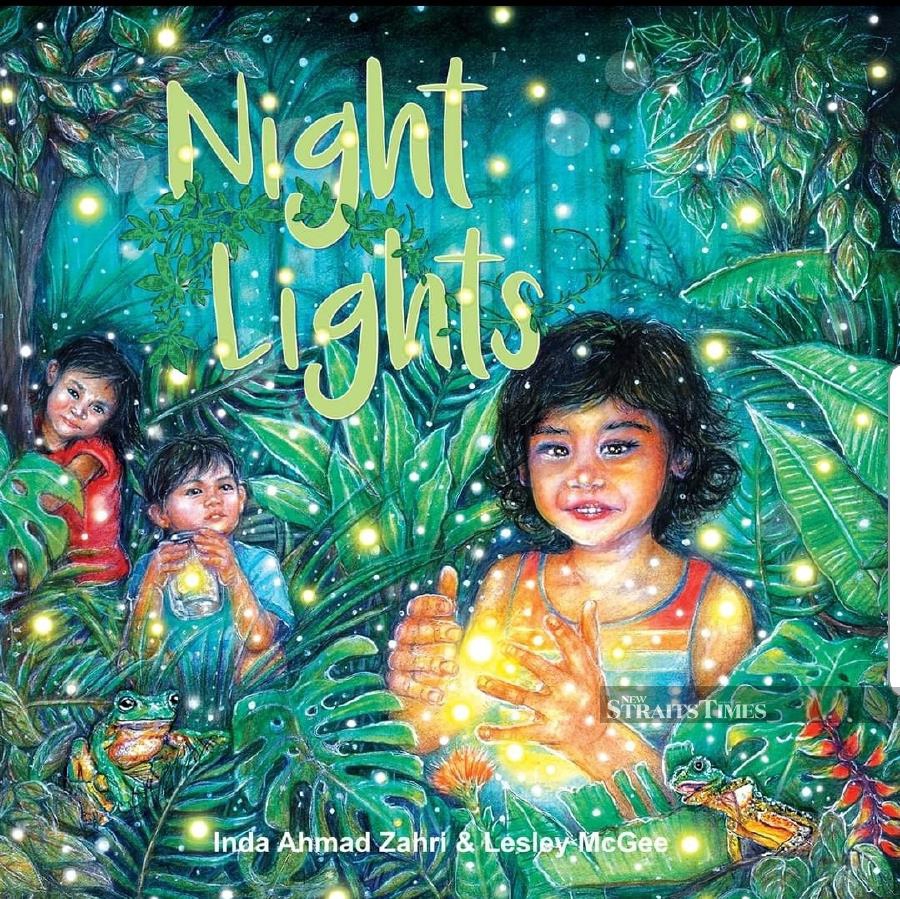

The desire to write was sparked while she was searching for suitable children's books for her then 2-year-old daughter. "I started seeking out Malaysian stories that would teach my daughter about her roots and culture. I couldn't find the ones that I especially liked. A lot of them tended to be very moral driven or textbook-ish."

Language, she explains, is so important, and given how much time kids spend in highly visual but verbally threadbare situations, books are a crucial balance. "It's not just a story we're offering them, it's the tools they need to tell their own stories, to tell to themselves, without too much cliché, and with some complexity. I thought to myself, 'Since I can't find the right kind of books for my daughter, why not write a picture book myself?" she adds blithely.

When she returned to Brisbane, Inda joined a free workshop on how to write a picture book at the local library. "I learnt so much!" she gushes enthusiastically, before adding: "Do you know that picture books are almost always 32 pages and that they should ideally be 500 words or less?" Then, shaking her head, she continues: "There was so much to learn!"

She had initially wanted to write a picture book in Malay, but a friend convinced her otherwise. "Why not write in English? People are more interested in different ideas and in diversity these days," her friend urged.

Inda joined different writing groups and submitted her stories for competitions. She also prepared manuscripts to be sent to publishing houses. "I really immersed myself into the nitty gritty of children's publishing. It felt as though a whole new world just opened up to me when I decided to get into writing seriously," she exclaims, eyes sparkling. "I started to write and write!"

BIRTH OF 'SALIH'

As she picked up her pen, the floodgates opened. There was so much happening in the world, and Inda decided to pen a story about the little refugee boy with his whole world tucked in his backpack.

"I was a young mother by then, and the plight of children displaced by war made me tear up. I wanted to spread a little kindness in the world, even if it was within the pages of a book," she explains with a heavy voice.

A little empathy, insists Inda, goes a long way. Most refugees, at some point in their lives were just living. They got up, went to work, hated Mondays. They cooked for each other, they had dreams and ambitions, and they wanted the same things as everyone else on earth wants. They wanted their loved ones to be happy, they wanted to grow old and comfortable. They have so much more in common with the rest of us than what separates us as people.

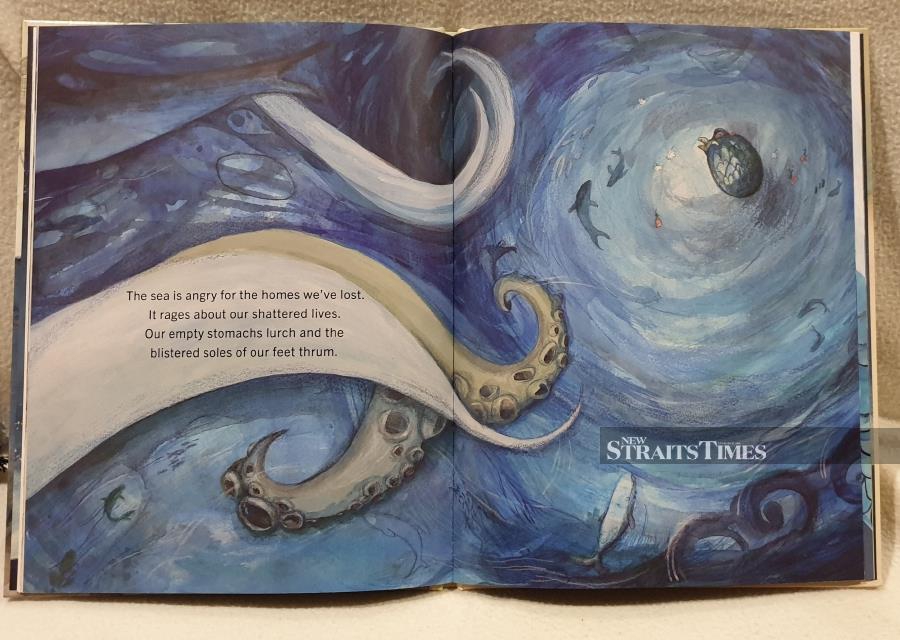

Salih's poignant story doesn't shy away from the harrowing life. "I wish I could forget… deafening blasts, white dust shrouding the sun, the sound of crying in the darkness." The evocative and lyrical text is brought to life through Anne Ryan's beautiful ethereal illustrations, the bleakness of the boy's past contrasting with the colourful images of his present.

She hopes that Salih can help raise awareness on the worst humanitarian displacement crisis our interconnected global community has experienced since World War 2. "It's really important to engage children with the world as it is. And the world right now is a very complicated place," she says.

Concluding, she offers a final thought: "There was a time when someone asked the Prophet Muhammad what they should do if they were to see an evil act. He replied, they should change it with their hands, and if they can't, then with their tongue, and if they can't, then with their heart, for that is the weakest of faith. In a way, I feel like writing this humble book is my weakest of faith."