The image can feel inescapable this time of year during Father’s Day: a man glancing at his reflection, running his hand over his newly smooth skin. Sometimes, a boy will be watching him, his face gazing up, his eyes wide with admiration and anticipation of the day he too will learn how to run the blade down his chin without making a cut.

Never is that association sold more aggressively than in June. Razors and brushes are featured in Father’s Day gift guides and arranged in store displays — neat little pyramids, stacked next to foams and creams and balms, all those male grooming products lined up in orderly rows. Maybe these presents are a way of saying thank you: for the everyday instruction, for the nudge toward adulthood, for just being there.

The things fathers pass on to their sons extend far beyond the dominion of the Y chromosome. Many of them are obvious: the physical features, the personality traits and the skills and talents so often attributed to DNA.

Then there are the less obvious inheritances, the links that later seem inevitable. The choices that, upon further examination, seem like they were shaped by some tenuous bond to the past. For bright-eyed 6-year-old Marc Aiden Fernandez, stepping into his very own exhibition hand-in-hand with his father Malcolm, bears testimony to their strong bond and shared talent. Marc, just like his father, is a talented artist in his own right.

The father-son duo is now currently exhibiting in a unique artistic collaboration entitled Dialects Of The Soul – Expressions at the Sireh Pinang Gallery in conjunction with Father’s Day. The exhibition is touted to be the first father-son artist pairing exhibition in this nation.

NURTURING AN ARTIST

While shaving is often presented as a masculine rite of passage passed from father to son, the inherited ritual between Malcolm and Marc is clearly evident – art. The self-taught artist and his son have between them, an extensive body of work that’s currently being showcased in Dialects of the Soul - Expressions.

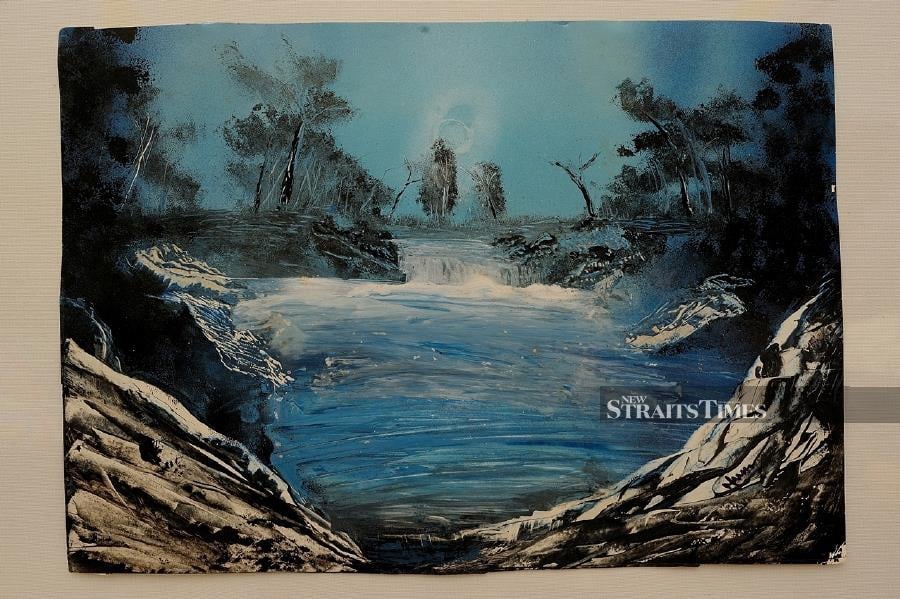

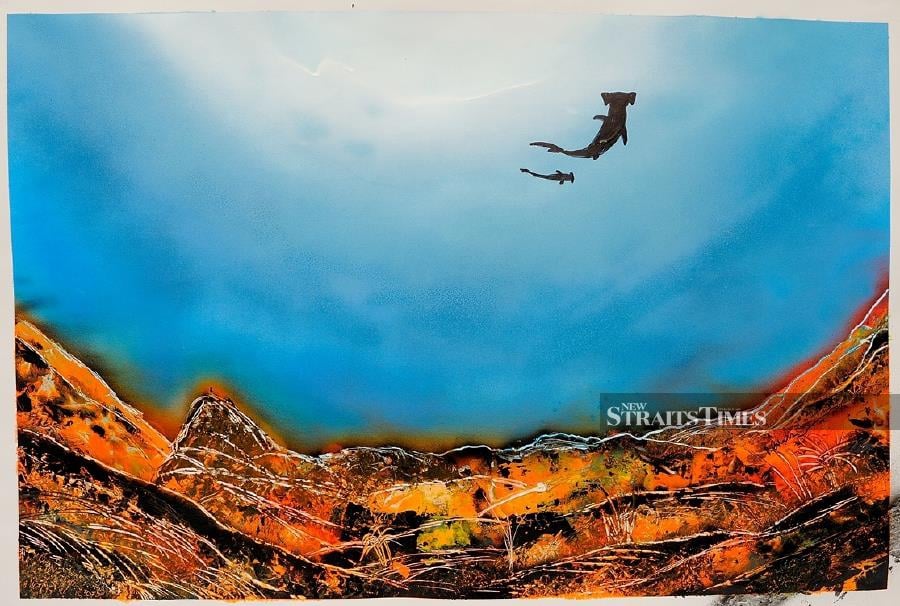

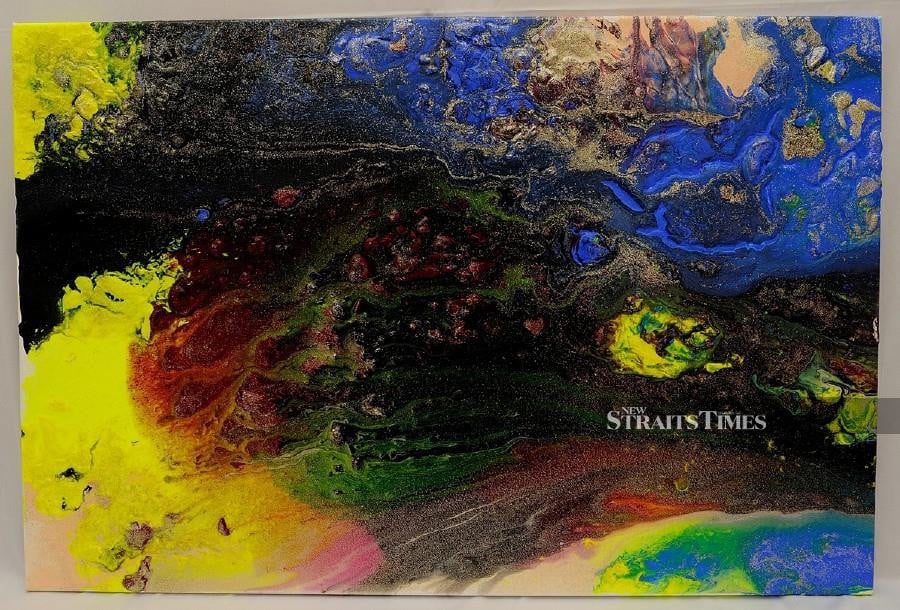

There is such a profound emotive thread that runs through Marc’s paintings. Swirls of colours that dominate the canvas speaks a language that goes beyond words. On average, a child could not “paint that”, even if first glances might suggest otherwise. Nor are the qualities of the abstract art only visible to people steeped in the art world – even untrained people respond to his paintings in some way. Sitting in a café with proud father Malcolm and sifting through the paintings, I am one of the latter. “They’re beautiful,” I murmur. “Thank you,” responds Malcolm, smiling. “You should meet him,” he says again after a brief pause.

He paints beyond his years, I point out. Marc’s natural aptitude towards art is remarkable, he agrees. “He used to watch me paint,” he says softly, smiling. Marc was an active toddler, recalls Malcolm. “He was known as the ‘Flash’, because he’d be crawling at lightning speed all around the house. He’d move so fast that even my maid couldn’t keep up with him!” But one thing caught his attention, and kept him still – observing his father paint out in the garden. With a thumb in his mouth, he would advance slowly towards his father, fascinated.

Quips Malcolm: “I could feel a pair of eyes boring into my back as I painted!” Every time he turned around, his little son would advance closer. “Pretty soon, he’d climb onto my lap as I painted. I’d allow him to touch the canvas, smearing the paint with his bare hands. He’d be squealing in delight!” Paint would soon find its way from canvas to his son, says Malcolm laughing. “If the paint was blue, he’d be resembling a little Smurf!”

As Marc grew up, he continued to sit with his father and observe him paint. Eventually he began schooling his son in art. The lessons were unplanned and intuitive. “They were moments of bonding, spending time together and doing something he was clearly enthusiastic about,” explains Malcolm. Marc wasn’t taught how to hold the paintbrush correctly at first, and there weren’t any rudimentary lessons for him. “I started teaching him when he was three. I never forced techniques upon him. He’d hold the brush any way he wanted to but eventually I’d gently suggest: ‘Bro, try holding it this way!’’ he recounts. He admits sheepishly to calling his son “Bro, dude or sometimes even buddy!”

Once Marc got used to it, he soon began to try painting on his own. His first drawing was a mix of crayons and colour pencils. The end result was amazing because he showed an inherent ability to mix colours. “What was even more amazing?” says Malcolm, “was the fact that he spent two and a half hours drawing! The only time he took a break was when he went to the washroom and when he demanded that I get him some cookies. He didn’t divert his attention until he completed it!”

Marc grew more and more involved in his father’s hobby. That’s when the arguments came in, points out Malcolm drily. “He’d be unhappy with my strokes and would insist I do things differently. When I didn’t, he’d throw the paintbrush in a huff and walk off trailing paint all over the house!”

It was time, Malcolm realised, that his son started painting on his own. “I want you to do your own painting,” he told his son. Marc’s first unassisted hand-painted piece using a wiper movement, was the aptly named Wiper. He was only four at that time. The song Marc was listening to at that time, was the nursery rhyme ditty The Wheels of the Bus, “…with the wiper going swish swish swish!” adds Malcolm, laughing.

The 47-year-old started his son on canvas. “I wanted to start him on the right footing,” he explains, adding: “When I realised he had a knack for painting, I decided to go the whole nine yards with canvases and proper paint tools.” So he didn’t do what other parents would do – get sketch books, colour pencils and even the ubiquitous colouring books my parents presented me when I was Marc’s age, I quip. “Well I’m not a normal parent!” he deadpans, grinning.

A SHARED INHERITANCE

Malcolm’s father was no ordinary parent either. The late Thomas John Fernandez believed in creativity too. “My father was inherently an artist,” he recalls softly. “We grew up playing with toys built by his own hands.”

Malcolm’s father worked at the oil rigs which invariably kept him from the family for two weeks in a row. Every time his father returned home, he would make up for the lost time he spent away. “My siblings and I had a ball whenever he came back!” he says. When he wanted a toy gun, his father would choose to make him one. “While my friends had guns that made sounds, mine actually shot pellets!” he recounts, laughing, before adding sheepishly: “You could guess I didn’t have many friends after that!”

His father taught him creativity. He’d tell Malcolm: “I could buy you a toy, but let’s see how we can make one instead.” His father taught him to explore when he was growing up. He’d take his children to the park, and tell them to pick up whatever that caught their fancy. “We’d pick up leaves, a sheaf of grass or twigs. When we came back home, my father would talk about the things we’d pick. He’d explain or even make up stories about them.”

There was a time, he tells me, when he came back from school one day and found that the stairs in his house had been repainted to resemble bricks. “I left the house with normal looking stairs but when I came back, they looked different!” he says, chuckling. He found his mother calmly reading in the hall, and without batting an eyelid, she said drily: “You father had some extra time today!”

Creativity ran in the family – Malcolm’s uncle (his father’s brother) was also an artist in his own right. And it’s apparent that creative DNA had been passed on to him as well. “I’ve always been painting and drawing for as long as I could remember,” he admits. Late at night, within the confines of his room, Malcolm would put on his headphones listening to heavy metal, thrash or rock music and paint.

Did you want to be an artist? I ask. “No, I wanted to be a doctor!” he replies, grinning. But somehow, his path veered off a different direction. The youngest of three siblings (“No, I wasn’t pampered!” he insists, before reluctantly adding: “Well… maybe just a little!”), he was convinced albeit reluctantly to pursue a career in law instead. “I wasn’t at all pleased at first. But then I attended my first lecture on Criminal Law and fell in love with the profession,” he recounts.

Throughout college, he kept at his art. “My father asked me one day to draw him a scenery. He gave me money and told me to buy what I needed. I was told to leave the drawing on his desk before I left for college,” recalls Malcolm, adding with a laugh: “I drew him a picture of a graveyard. It must have been my heavy metal influence at that time. Needless to say, he wasn’t very impressed!”

Still, his father was his best friend. “He really was,” reveals Malcolm softly. “And I hope to raise that bar with my son, by being his best friend.”

RAISING MARC

While other men were dreaming of making their first million, or travelling to exotic places, Malcolm had always dreamt of being a father. “It’s what I always wanted to be,” he admits. So when his wife was pregnant with Marc, he was ecstatic. “I fell in love with Marc almost instantly,” he reveals. “I did the whole nine yards – doctor’s visits, playing music, talking to my unborn child and when I ran out of words to say, I’d read him my law reports!”

Is there makings of a lawyer in Marc? I tease. “Well for the longest time, he wanted to be a lawyer like daddy. Now he wants to be a race car driver!” he responds chuckling while shrugging his shoulders.

Still, the shared love of painting has brought them closer than ever. “He’s my biggest fan and critic,” he says, pride lacing through his voice. “He tells me, ‘Daddy, maybe you should do this differently,” and then there are those precious moments when he says, ‘Your paintings are beautiful Daddy. That’s all that matters.’”

It’s amazing, he shares, to watch his son paint. “He knows exactly what he wants to paint and he doesn’t like me to interfere,” says Malcolm. “He mixes his own colours, and he only has me around to bring him his palette and assist him when he needs it!” As Malcolm regales me with vignettes of Marc’s personality, his eyes soften and any remnants of the confident corporate lawyer persona vanish. Instead, it’s a doting father that smiles across the table, nursing his cup of coffee.

“You’ve got to spend a lot of time with your child,” he remarks, adding wistfully: “Time flies so fast.” Just the other day, Malcolm tells me, he asked his son if Daddy was still his ‘bro’. The answer was a no, he tells me a little sadly. “Marc told me, ‘No Daddy, you’re not my ‘bro’. I’ve got ‘bros’ at school now!’” He notes that Marc is growing up, and there will be a time, he says, that it would not be cool to hang out with his parents.

“But he will always know that his dad has made that monumental effort to be with him and nurture him,” he says softly. “It teaches Marc one thing… that when one day when he grows up to be a father, he will raise the bar. My dad was my best friend and what I’m doing with my son is to raise that bar.”

Father’s Day is a reminder of the traits and rituals that we pass down, often unwittingly, through DNA and demonstration. From art to the teenage rite of passage not too far in the future – shaving, there’s still an adventure ahead for both father and son.

Dialects of the Soul – Expressions

When: Until July 20

Where: Sireh Pinang Art Colony, Antara Residence, Jalan P5, Precinct 5, Putrajaya

For more information, please call 010 7707343