“THIRTY minutes! Remember, I’ll be back in 30 minutes! Then it’s straight to the airport.” Those were the last words from my friend, Patrick Lo, before he drove off towards the nearby town of Tin Shui Wai to attend to his errands.

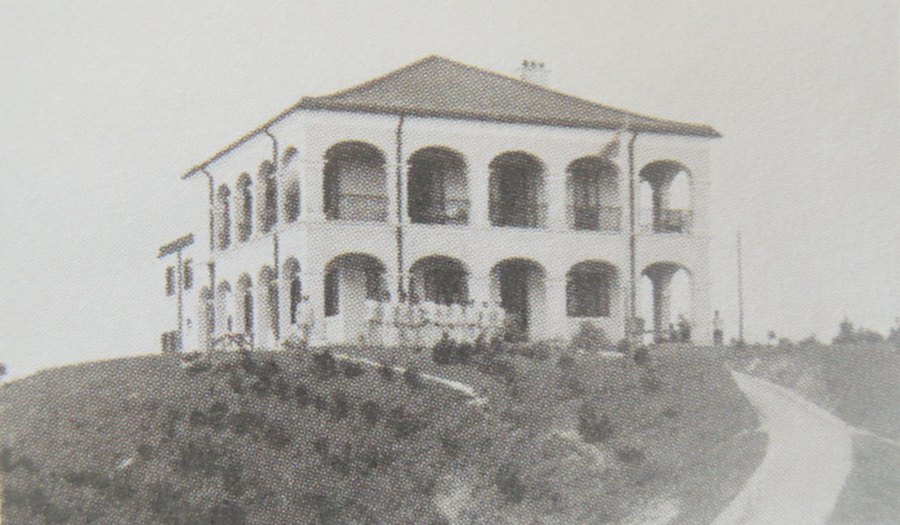

Walking up the slight incline, past a partially open pair of huge wrought iron gates, I make a beeline for an imposing double storey building. This century-old structure once served as the Ping Shan Police Station. Aware of my deep interest in heritage and culture, Lo had kindly squeezed in this quick visit to Hong Kong’s New Territories before I headed home.

Mentally reminding myself to keep track of time, I quickly head over to the main entrance only to find it securely locked. It’s only at that moment that I notice a small signboard hanging by the side of the main door informing visitors intending to view the Ping Shan Tang Clan Gallery to proceed to the annex building at the back.

Confident of having more than enough time to view the exhibits, I decide to take more photographs and record the many interesting features on the building’s facade. Standing back some distance, it dawns on me just how grand and imposing this colonial era structure must have looked when it began operations back in 1902.

PING SHAN POLICE STATION

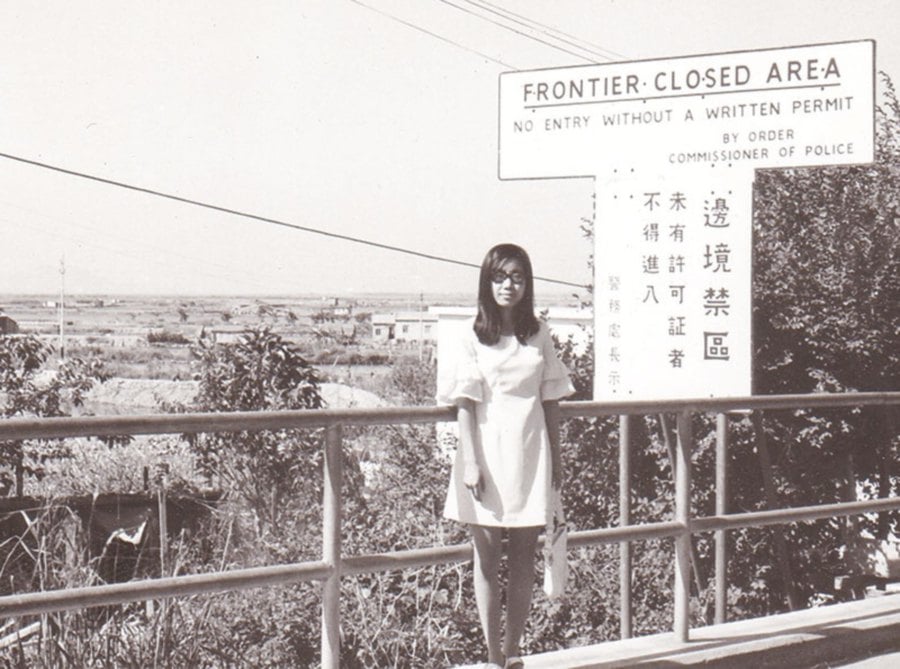

Perched at the top of the solitary hill beside Ping Ha Road, the station’s height advantage gave border policemen on duty in the past a clear line of sight of the surrounding countryside as well as an unobstructed view of the demarcation zone separating the British colony at that time from China.

Before the colonial police force in Hong Kong was formally established in 1844, law in the colony was enforced primarily by the soldiers belonging to the British East India Company. The first large scale police station in Hong Kong was built in Central in the late 1840s when local law enforcement body became more established and funds were made available.

As the police force gradually became larger and the Hong Kong population began to spread further, more police stations like this one here in Ping Shan became a necessity. The colonial era buildings found throughout this former British colony all share a common attribute. They all have functional features which are specially designed to adapt to Hong Kong’s hot and humid sub-tropical climate.

At this point, I recall reading several reference books which mentioned that there were no “professional architects” in colonial cities during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And Hong Kong was no exception. Building design and planning tasks were placed under the auspices of engineers or draughts men from the Royal Engineers Corps who, without proper professional training, relied heavily on and copied the reproduced images of existing buildings found throughout the Empire as closely as they could.

The former Ping Shan police station’s facade with its grand arcades and cool porches immediately remind me of similar looking colonial era buildings in historic Kuala Lumpur and Singapore. Shifting my sight from the well maintained window louvres, I take a quick glance at my time piece. A good 15 minutes have passed by in a flash. It’s time to head over to the gallery.

A WALK THROUGH HISTORY

The Ping Shan Tang Clan Gallery is housed in a smaller and less elaborately-designed building compared to the one I saw earlier. Located on the north side, this Annex block has white walls, open verandahs and a pitched Chinese-tiled roof complete with prominent chimney stacks.

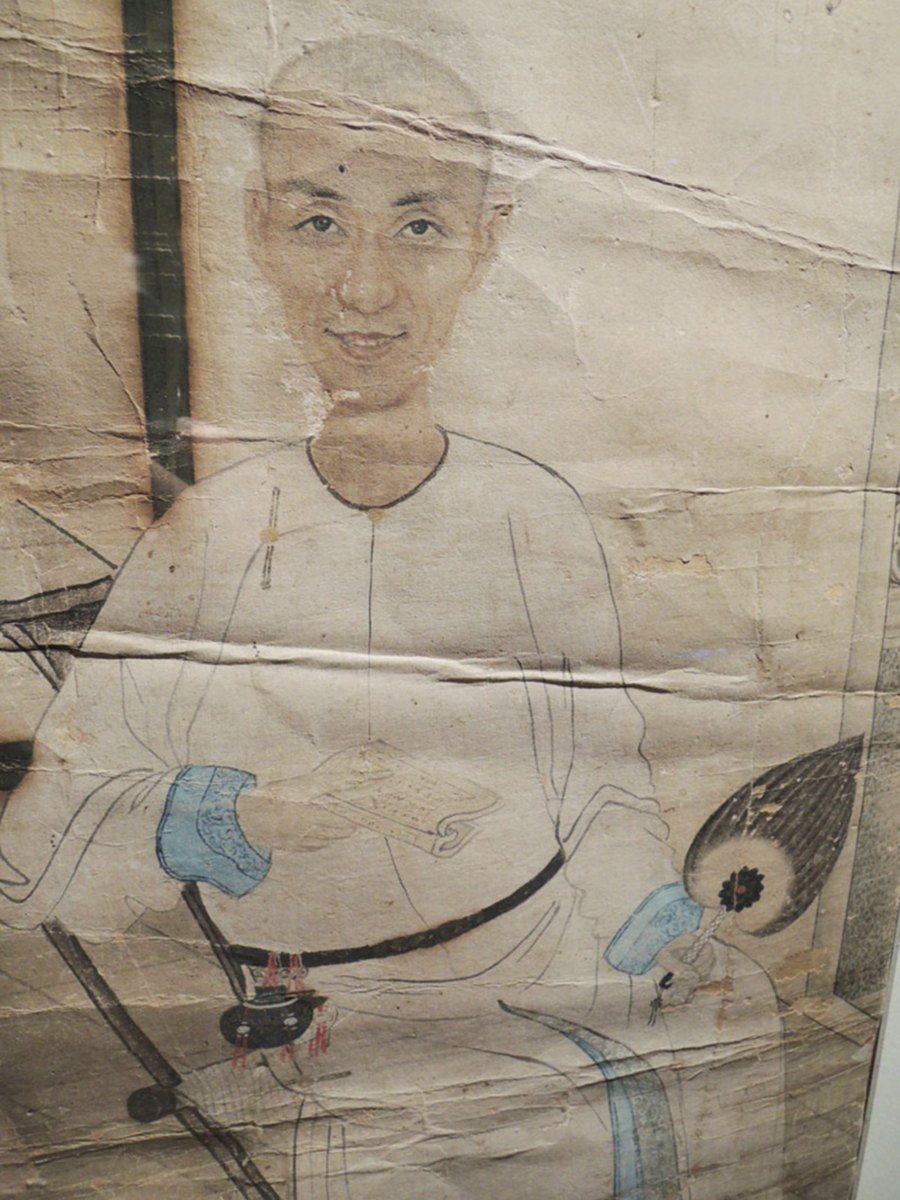

Apart from the gallery, visitors can follow a designated heritage trail which links nine well preserved historic sites in the vicinity. The first few exhibits by the gallery entrance traces the Tang clan lineage right from the time when the group first settled in Ping Shan around the 12th century. The clan, headed by Tang Yuen-ching, established three wais (walled villages) and six tsuens (villages) around this area, which itself is located within the historically significant district of Yuen Long.

As the Tang clan influence and prosperity grew, these industrious people began building numerous halls, temples and pagodas for ancestral worship, clan gatherings, festival celebrations and pursued the advancement of education among the younger generation.

Legend has it that Yuen-ching and his son made the decision to settle in Ping Shan during a chanced discovery while on a deer hunting expedition. They were immediately captivated by the area’s excellent feng shui attributes. The mountain-sheltered fertile farmland with its abundant water supply was a picture of peace and tranquility compared to their troubled homeland.

Best of all, the general landscape gave the father and son the illusion of a mounted rider turning around to gaze back. The two men thought that this perceived image conveyed an auspicious message of sons and grandsons returning home after achieving prosperity and fame.

Venturing deeper into the inner bowels of the gallery, I’m especially attracted to the displays that feature artifacts used by the early Tang people. These items include ceremonial robes, wedding paraphernalia and uniquely-shaped receptacles for ritual offerings. The accompanying descriptions mention that the Ping Shan Tang clan members still practice some of these culturally-significant customs right up to this very day.

These elaborate ceremonies not only symbolise the local folk culture but also reflect the traditional and unique characteristics of life in Hong Kong’s New Territories.

The remaining exhibits provide a very comprehensive summary of the 11 sites found along the heritage trail. This special walkway, inaugurated on December 12, 1993 as the first of its kind in Hong Kong, meanders through the ancient Tang villages of Hang Mei Tsuen, Hang Tau Tsuen and Sheung Cheung Wai.

Among the significant places are the Shrine of the Earth God and Tsui Sing Lau Pagoda (Pagoda of Gathering Stars). The former is the temple where the Tang villagers give offerings to To Tei Kung (Earth God) for the annual bountiful harvest and for protecting them from harm.

LAND AND HOME

The 600-year-old Tsui Sing Lau Pagoda is the only ancient pagoda in Hong Kong. This hexagonal-shaped, triple storey green brick structure stands 13 metres in height, distinguished by unique eaves between each level. The locals believe that this feng shui structure serves to ward off evil spirits from the north and its auspicious alignment with the distant Castle Peak helps to ensure success for clan youths in the important imperial service examinations held during ancient times.

A display featuring several century-old land records catches my eye. I’m intrigued by the unique land management system used by the Tangs. Relying heavily on farming and animal husbandry for their livelihood, the people here effectively manage their lands in a manner akin to a modern-day fund manager.

In the past, the Tangs divided their lands into two categories — communal and private, and managed them accordingly. Communal land belonged to the clan exclusively and couldn’t be sold without prior consent from the elders. These shared lands were divided into equal portions and rented out to clan members.

The money from the rent were used for the betterment of the community like scholarships or bursaries. The remaining funds were kept as savings only to be dipped into during times of dire need. Private land owners were given free rein to do as they wished with their property. The only provision is that a portion of their land would revert to the community when the original owner passed away.

The Tang clan’s growing prosperity inevitably attracted the attention of pirates who regularly plagued the Yuen Long district given its proximity to the Pearl River Delta. Using bricks, granite and wood, the villagers built secure homes which, together with the streets of the villages, were laid out in a manner that made it easier to defend in times of pirate raids. High walls ring entire settlements to help deter attacks.

Apart from securing their villages from marauders, the Tangs also placed great effort in designing comfortable homes for themselves and their families. Photographs of Tang houses with open courtyards remind me of this similar feature found in pre-war shophouses back home.

These functional open areas, usually found in the middle portion of the homes, allow fresh air and sunlight into the otherwise musty and dark interiors. Today, some of the villagers can still be seen living in these traditional homes, their century-old furniture and household implements still intact.

I reach the end of the exhibits with just mere seconds to spare. Walking out into the warm summer sun, I stand at the edge of the hill to take a long look at the distant countryside, trying hard to see if I can figure out which parts look like a horseback rider.

At that moment, I notice a large cemetery by the nearby hill slope and begin to wonder if that’s the resting place of Yuen-ching and his son. Before I can take another step forward, I hear someone calling my name. It’s my friend Lo. Hopefully I’ll have another opportunity to come back here again and uncover the remaining wonders in Ping Shan.