THE French, they have a love affair with North Africa. Maybe it’s the sun, the sand, the bright colours of the fabric, the beaches, the women, the camel or the goat.

Maybe because opposite attracts. After all, North Africans are friendly and warm and are not limited to garlic in their cooking, and have never been known to force-feed corn to their camels or goats just so they can have swollen liver for making pate.

Don’t get me wrong, I love the French and how they don’t really notice it when we snigger under our breath at them, and I love that they think they make the best cars in the world.

That said, they have come up with some gems like Citroens Traction Avant and DS, the Renaults 5 and Mégane, Peugeots 504 and 205, and the odd Alpines and Venturis.

What we do get out of the French love affair with North Africa are stuff like the Paris-Dakar rally, now just called the Dakar, and really hardy cars.

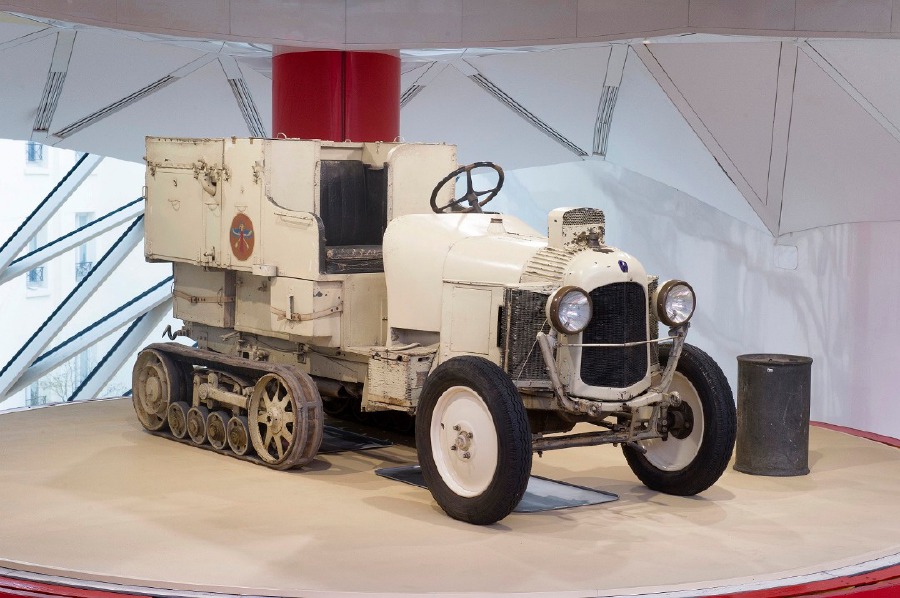

The Scarab, a monstrosity of parts which matches Mary Shelley’s lightning-powered beast, is one of the most interesting result of this.

In 1922, this became the first vehicle in history to cross the Sahara on an expedition initiated by André Citroen himself and was rather inappropriately named Croisiére Noire, which Google translates into “Black Cruise” or, perhaps, “Black Crossing”. The Scarab looks so much in the way how the camel looks; both were designed to look at the needs of the job at hand and the vehicle was designed to suit those needs with not even half an eye on aesthetics. The base car was the Citroen Type B, the second model ever produced by Citroen.

Apart from being a nifty little car, the Type B was among the first cars to be produced using mass-production methods at Citroen’s factory in the centrally located 15th district of Paris, which would basically be in the shadows of the Eiffel Tower, if the sun sets in the North Pole.

The Type B is not a powerful car in the modern sense, but in those days, it was considered pretty frisky and was classified as having 10 fiscal horsepower, but 20hp if measured on the dyno. Fiscal horsepower was simply a way of calculating taxation and it was based on the piston diameter.

Why piston diameter? Well, it has to do with work generated according to pressure and piston size, and just to scare half of you away I will put the formula for it below.

P = (n * ( ? / 4 ) * D2 * L) * p * N

I guess it was a simple way of calculating taxes, but it was also a nice little way for manufacturers to maintain low taxes while increasing power output in other ways, like increasing engine speed and effective pressure.

The 1920s is for the internal combustion car like the 2020s is for electric cars; everyone was busy trying to prove that their technology is the most durable and can withstand the worst of environments and abuse, and can go the furthest without breaking down and crying.

Rolls Royce built halftracks, so did Mercedes Benz and, of course, Volkswagen built the K¸belwagen for friends of Jojo Rabbit’s imaginary friend.

They built halftracks because that was the epitome of go-anywhere, the low pressure that the driven track exerted on the ground meant that it should not get stuck even in the softest and mushiest of bogs.

To this day, the route of Citroen’s Black Cruise is still considered amazing and even modern vehicles with the latest all-wheel drive technology is not guaranteed easy passage across the world’s largest ocean of sand.

The truth is, the expedition never led to any form of motorisation of the Sahara crossing, because despite our best attempts, no one has come up with something better than a camel for traversing the world’s biggest sandbox.

Next to salt water, sand is one of engineering’s biggest enemy. Those miniscule rocks can get in between surfaces and scratch them beyond repair, make their way under improperly tightened caps and wreak havoc with pistons, bearings, pumps and whatever else that moves. While tracks do exert low pressure and keeps the vehicle on the surface, they are clunky and do not turn well and cannot self-balance on uneven surfaces. Camels and their wide toes, lanky legs, slow gait, humpback fat store, fluid preserving respiratory system and near perfect-seal against sand is superior in every way.

That is why the camel remains king of desert transport and is still in use today without fear of any challenger.

However, that is not to say that the 1922 crossing was not fantastic. It was and continues to amaze Land Cruiser and Land Rover drivers till today.

To celebrate this fantastic journey, Citroen has built a replica of the Scarab with the help of engineering students in 2016. The build also coincided with the centenary of the Double Chevron and French engineering doggedness.

I think the world needs more of these rather pointless expeditions just so that we can push ourselves and amaze others and inspire the world to try something crazy themselves.

After all, all of modern civilisation was built on crazy ideas that someone dared to think and try to carry out.

That is the reason why we must celebrate every crazy idea that comes out.

Maybe we should persuade one of the local car companies to build polar expedition vehicles.